- Film

Docs: “Art for Everybody” Explores the Life of Wildly Successful but Critically Derided Artist Thomas Kinkade

If one stopped a hundred people on the street in the United States and asked them to name the most popular and successful artist of the past quarter century, it’s unlikely more than a few — if any — would name Thomas Kinkade. And yet sales estimates claim that at his peak, one out of every 20 homes in America owned a copy of one of his paintings.

The interesting new nonfiction film Art for Everybody, which enjoyed its world premiere at the South by Southwest Festival on March 13 in the Documentary Spotlight section, unpacks the life and outsized impact of Kinkade. In building a mass-marketed empire that would crest with well over $100 million in annual sales, Kinkade achieved a further realization of Andy Warhol’s factory-model dream — despite (or maybe even because of) peddling works lambasted by critics as garish, simplistic, grossly sentimental and twee.

While tracking largely as a biographical portrait, Art for Everybody most succeeds in illuminating society at large by way of two aspects connected to its subject’s life. Firstly, it serves as a cautionary lesson about the potential cost of commodification — the constrictive nature of embracing an alter ego or brand that doesn’t allow for a fuller public presentation of one’s true personality.

Secondly, embedded specifically within the story of Kinkade’s rise to incredible heights is the fact that his bellicose acceptance of the war against critics and the art establishment served, in a way, to foreshadow the pervasiveness of cultural division in American life, when every single thing not understood or personally enjoyed must be cast as negative in the starkest terms.

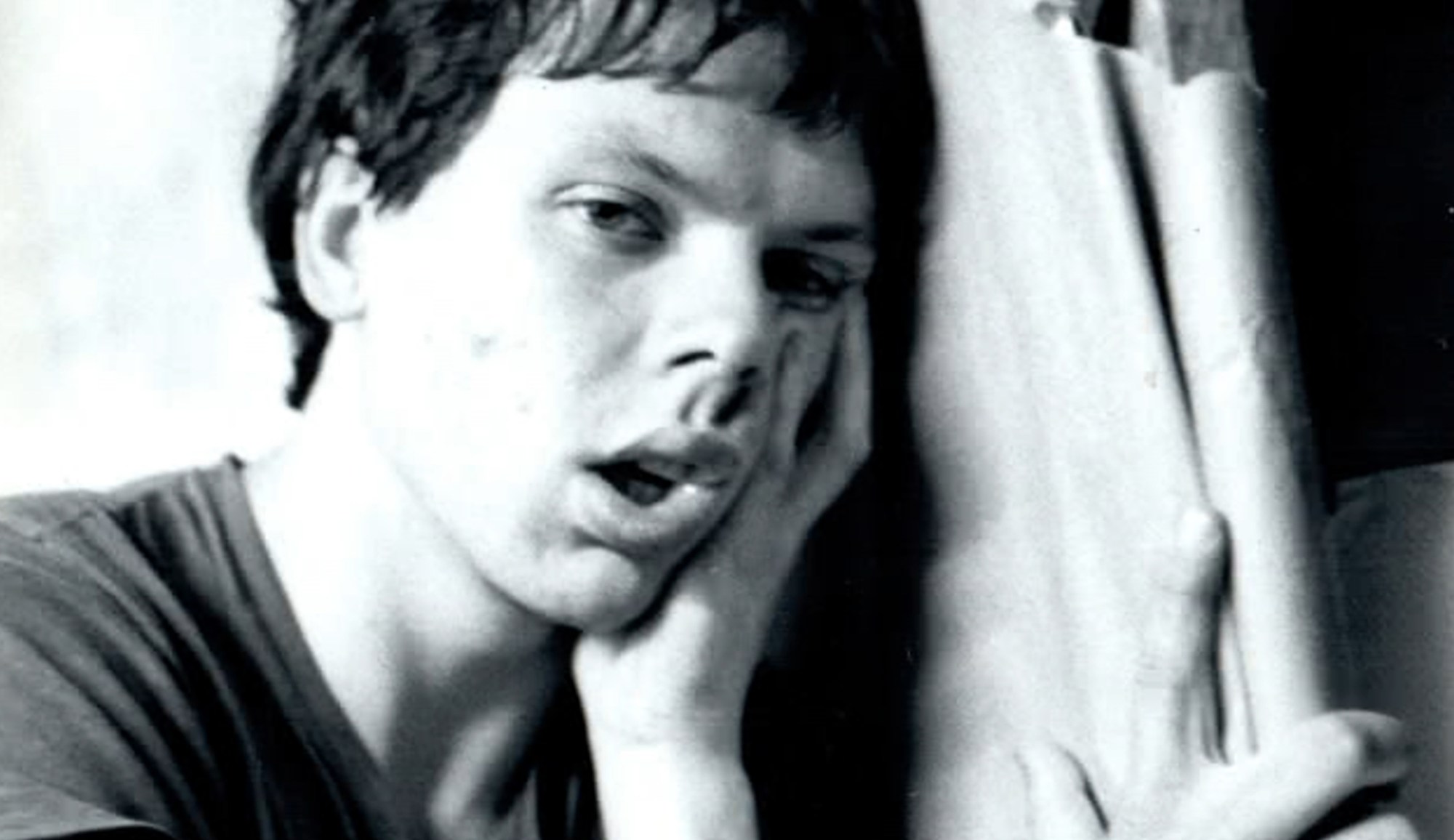

Kinkade grew up in the small town of Placerville, in northeastern California. His parents divorced when he was a child, which left Kinkade with an intense sense of shame about both his figuratively broken home and very modest, hardscrabble upbringing, according to his brother Patrick and sister Kate. Not long after college, Kinkade secured a job creating background paintings for his 1983 animated dark fantasy epic Fire and Ice. Kinkade delivered fabulously on that job, according to director Ralph Bakshi, but also wanted to then strike out on his own.

Despite his education and expansive formal training, Kinkade branded himself as “the painter of light,” and set about pumping out art of unambiguous affirmation — idyllic cottages, pastoral landscapes, and occasional cityscapes. His paintings would be art, priced and produced at scale, for “regular” people.

In 1992, he would open a mall store dedicated to his work. Powered by QVC appearances that bolstered his image as a pious Christian living an untarnished life, Kinkade hawked not only prints but collectible plates, mugs, sofas and recliners. He even opened a community of homes built around his brand. An economic downturn would eventually arrive in 2002, followed in short order by lawsuits from franchise owners of his signature galleries alleging fraudulent business practices.

Art for Everybody is built mainly around interviews with Kinkade’s four adult daughters and ex-wife Nanette. Other figures, though, help provide a contextual frame for his work, and existence as a type of hybrid painter-as-performance artist. These interviewees include former business partner Ken Raasch, fellow artist Jeffrey Valance, writer Susan Orlean (whose 2001 New Yorker profile helped put a target on Kinkade’s back with the art world intelligentsia), and Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight.

The most recent point of comparison for Art for Everybody may be 2021’s Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed, another nonfiction portrait of a massively popular American painter. There is enough overlap in subject matter, and also how each man grasped the benefits of a pat packaging, that viewers of that Netflix documentary will certainly find reward here.

Whereas the affable, Afro-ed Ross, though, was quite bad at business, Kinkade was always shrewd. This is established from the movie’s very beginning, which opens with a voice recording of its then teenage subject pondering the merits of achieving the lasting greatness of someone like Vincent Van Gogh if it means living in destitution.

Critics might deem Art for Everybody perhaps a bit too deferential to its subject, and accurately point out that its details of downward spiral remain a little hazy, in need of racked focus. Kinkade’s family makes vague reference to him being difficult to live with, and while they’re certainly forthcoming about his drinking problem and trip to rehab, director Miranda Yousef never really seems to identify Kinkade’s rock bottom.

The mugshot from a 2010 DUI arrest is shown, but the incident is only referenced in passing. A depressive episode in college, precipitating a transfer from the University of California, Berkeley to Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, is speculated about, but raises only more questions.

Art for Everybody, in other words, sidles up to addressing the psychological consequences of becoming massively popular for a persona that maybe isn’t false but also is limiting. But it doesn’t seem to quite know how to resolve the dilemma of how Kinkade presented outwardly with the man who left, upon his death, thousands of paintings and sketches of different styles in his personal vault.

If the amorphous nature of Kinkade’s demons helps the film arguably retain a broader relatability, it also leaves him somewhat in limbo as a tragic figure — sentenced to the same unknowability, and inability or unwillingness to showcase the full range of his personality and talents, that seemingly haunted him in life. Perhaps that, however, is actually an appropriate portrait.