- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Dino Risi and His Beloved Monsters

Film Bios is an occasional series reviewing autobiographies of notable filmmakers.

Four years before he passed away in 2008 at age 91, Dino Risi published I Miei Mostri, a sort of memoir – or confessions as the Italians prefer to call it – actually an eclectic mix of miscellaneous recollections of his long life whose title, of course, refers to one of his most famous films, The Monsters (1963).

The book was translated into French in 2014 but never into English. What a shame. With his compatriots Luigi Comencini, Mario Monicelli, and Ettore Scola, he was one of the four musketeers of the Commedia all Italiana, the masters of comedy Italian style that reflected the golden years of Il Boom, that economic miracle that swept the country from the late fifties to the seventies.

From The Easy Life (Il Sorpasso, its French title was Le Fanfaron) to Scent of a Woman, he left an immense legacy with several iconic films, some classics and also many minor ones. After all, he made more than 50 without counting his work for television. However, he deliberately never mentions one single title in his book! Something that will surely baffle and disappoint the cinephiles.

Don’t expect a typical autobiography from Risi. If at the beginning he declares that “Cinema is the best job in the world”, in the end, he doesn’t talk much about it. Confessing that, most of the time, “the truth is that I believe I did many of my movies without being conscious of doing them. I was sitting by the camera, in my director’s chair, and I would say “Action”, “Let’s go!” But I was thinking about something else. I was impatiently waiting to be done with the day’s work to be again alone with myself. I was thinking about everything but the film…about another story, other places, other actors. The film I was shooting was already metabolized, it was done, I could see it and it bored me. I could not linger on it any longer….”

Quite a revelation. And he candidly distilled many more, in non-chronological order, in one 150 texts, some barely a few lines long, others extended to two or three pages. Many are colorful vignettes, often comical, outrageous, bittersweet, all painting a rich palette of scattered memories.

Nothing really predestined Dino Risi to become a screenwriter and filmmaker. We learn that his father was the doctor of the Mussolini family, long before Il Duce rose to power. At age six, Risi refuses to attend religious instruction classes, declaring himself as a free thinker to his teacher. In school, he met Alberto Lattuada, who became a lifelong friend. He studied medicine, then psychiatry. Cinema came by accident. He made a name for himself as a director in 1955 with The Sign of Venus, starring Sophia Loren. Seven years later, The Easy Life with Vittorio Gassman and Jean-Louis Trintignant becomes a huge hit.

Many more would follow, until his last one in 1996. But Risi remarks: “If I look back, I see more remorse than success.” No wonder one gets the feeling that he doesn’t seem to like his films very much. In any event, he refuses to watch them again. When one is shown on the small screen, he’s slow to recognize it as one of his; when he finally figures it out, he finds it too long and turns the television off.

He prefers to resurrect the ghosts of many friends and colleagues, his “monsters”. “They are all gone now”, he writes, typing away on his old Olivetti Lettera 32. He remembers them as irresistible and complex monsters, with their idiosyncrasies. Selfish, brash, irritating, but also profoundly human, full of charisma, charm, generosity and so fun to be around.

In life, these actors seem to always be playing their own part. Il Mattatore, Vittorio Gassman of course with whom he did more than a dozen movies, mainly described as “depressive and an alcoholic”; Lattuada and his obsessive erotomania; Ugo Tognazzi, the unabashed womanizer; Nino Manfredi.

And Alberto Sordi. While shooting a movie in Venice, he accompanied him one night to Il Dollaro, an establishment catering to gentlemen in search of paid female companionship. It was 1958 and the landmark Merlin law had just been voted, which ordered the closing of all brothels in Italy. The actor wanted to throw a little farewell party to celebrate the end of an era with the regular customers and the ladies who had serviced them for so long. Champagne and tears were de rigueur until the next morning early hours. The memory inspires Risi to reminisce fondly about another brothel, Via San Pietro in Milan.

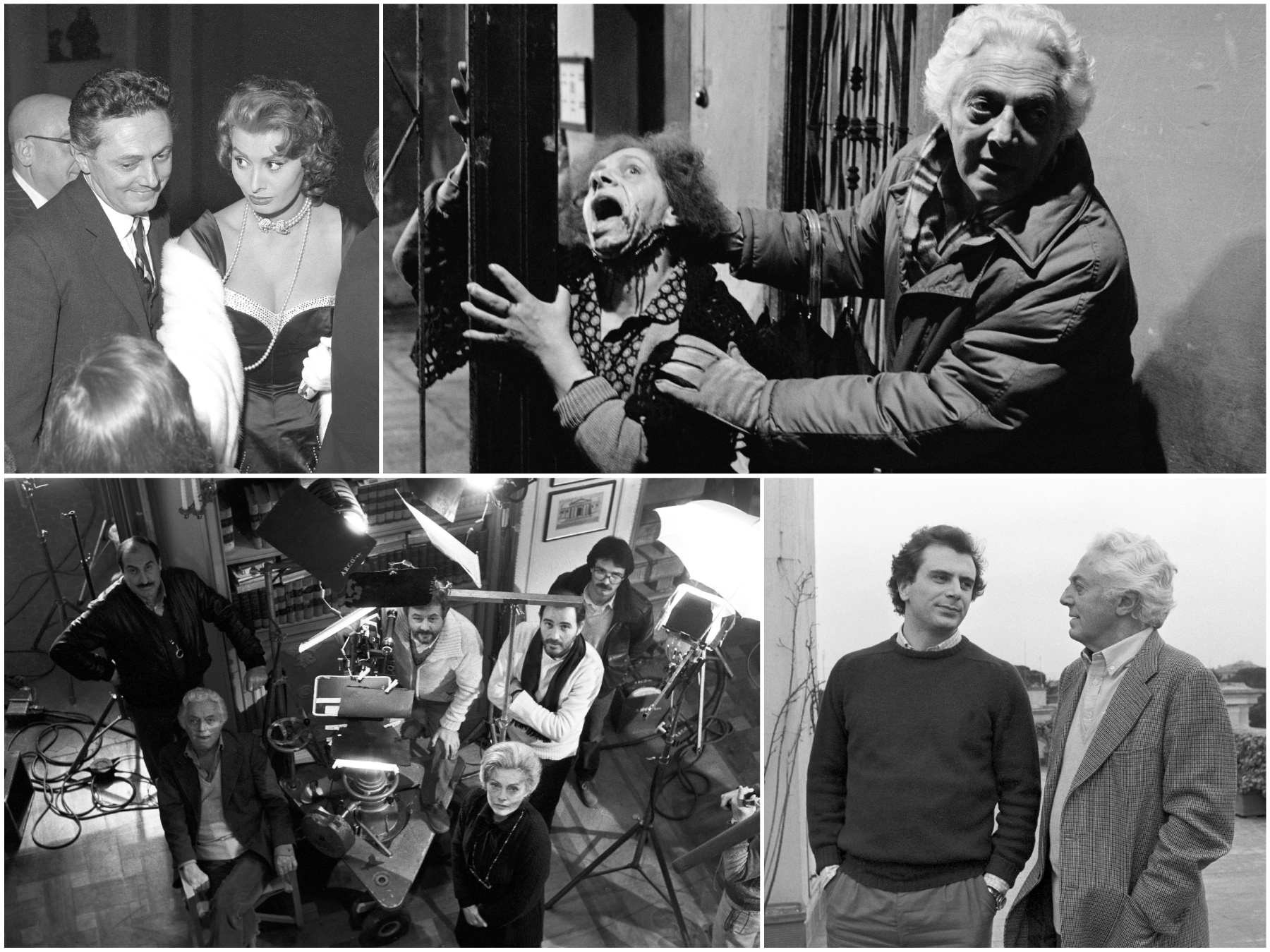

“If I look back, I see more remorse than success”- the life of the accidental filmmaker: (from top left) with Sophia Loren attending the premiere of the film Scandal in Sorrento, Cinema Corso, Rome, 1955; showing how it’s done on the set of Fantasma d’Amore, 1981; his son Marco on the terrace at home, Rome,1983; with Virna Lisi and the film crew on the set of the TV mini-series …e la vita continua, 1984.

sygma/mondadori/getty images

Other important figures of the past continue to appear in an almost kaleidoscopic manner. Love affairs come into focus, never idealized by the filter of time.

In 1941, a 24-year-old Alida Valli seduces him on the set of Mario Soldati’s An Old-Fashioned World. They became lovers. In their room one evening, the couple noticed smoke coming from a rolled carpet. The jealous Soldati had hidden into it to spy on them and…had lit up a cigar! Later, the actress waves him goodbye at a train station. “I’ll call you tomorrow,” Risi adds with deadpan humor. “I only saw her again 60 years later when we both got the Vittorio de Sica’s Prizes from President Ciampi !”

In 1961, he has an affair with Anita Ekberg. One day, they are on a speedboat zipping by a cargo ship coming from Malmö, Sweden. From the deck, the horny sailors wave at the voluptuous star of La Dolce Vita. On an impulse, the Swedish bombshell gets totally naked. “You knew it’s my town”, she tells a stunned Risi. “I sure do owe it to those poor kids!”

On the set of Fantasma d’Amore in 1981, Marcello Mastroianni has to do eight takes to kiss Romy Schneider. His comment? “And I get paid to do this!”

Catherine Deneuve sends him an insulting letter. He doesn’t reveal why exactly. It may have to do with the way he allegedly treated her during the filming of The Forbidden Room in 1977. The Red Brigades threatened him, too.

Risi sprinkled many aphorisms along the way. “Television is much better than cinema. One always knows where to find the toilets.” Another one: “In a hurry? Drive with Pirelli, shoot yourself in the head with a Beretta, and masturbate thinking about Sandrelli.”

It’s difficult for the reader not to be seduced by his joyously hedonistic and facetiously rebellious approach. He talks about his dreams, his moments of bitterness, his frustrations, his nostalgia for the old times. Always with some detachment, “modestamente” like Toto would say. Never taking himself too seriously. He shares the addresses of his favorite restaurants. Why not, after all? Special praise for Otello alla Concordia in Rome, a trattoria not far from the Spanish steps.

He writes a moving letter as a distant father to his two sons, Marco and Claudio, both filmmakers. And when he happens to see some of the work of Nanni Moretti, he can’t help blurting out: “Next time you appear on the screen, move a bit to the side, so to let me see the picture.”

Any regrets? “I would have liked to be irresistible like Cary Grant, intelligent like Einstein, and be able to dance like Fred Astaire.” Instead, he was able to make us laugh.

He claims death doesn’t scare him and never has, because, forever the optimist, he anticipates “it will be superb and rich in surprises…”

At this stage of his life, he enjoyed watching reruns of 81/2 and Stagecoach on television. And spending time reading Chekhov and John Fante. Before hanging up the telephone, he is careful to modulate the way he says his ciao, in case it would have been the final one…

As his friend, Ettore Scola could have said, with an appropriate variation on the title of one of his most famous pictures: Ti abbiamo tanto amato, Dino. Ciao, then.