- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiography: Preminger’s “Otto-Biography”

Film Bios is an occasional series reviewing autobiographies of notable filmmakers.

“The 21st of October 1935 was my second birthday”, writes Otto Preminger at the very beginning of his memoirs, published in 1977and simply titled An Autobiography.

The 30-year-old Austrian-born stage director was standing on the deck of the French Liner Normandie passing by the Statue of Liberty, about to start a new life in America. And it was worth celebrating. Six months earlier in Vienna, he had been recruited by two of Hollywood’s most powerful men, Joseph M. Schenck, chairman of 20th Century Fox and the studio’s other mogul, Darryl F. Zanuck. The movie capital of the world would be his new playground as a filmmaker, the beginning of a prolific career that would last for the next forty-four years.

Incidentally, two of his countrymen had already settled there, Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder. But Preminger is mum about the former and dismisses the latter with one short sentence and a trivial anecdote, never alluding to the fact that …he had been directed by him in Stalag 17! If there were some resentment, or simple professional indifference, between the three Austrians, he chooses not to say, deliberately leaving that enigma unanswered. But it is just one of many that can be noticed through his book as he takes the reader down memory lane. Starting with his childhood, his acting debut on stage at 12, his work with Max Reinhardt, his early success as a theater director in his home country.

The beginning of his Hollywood life starts on the very night of his arrival, with an appropriate first-class welcome from his new boss. “A glamorous party was given in my honor. I met Charlie Chaplin, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Louis B. Mayer, Norma Shearer, and Irving Thalberg.” But reality soon settles in. Zanuck doesn’t feel Preminger is yet ready to direct, so he makes him watch other directors at work for several months. Their collaboration had many ups and downs. They would often clash, notably on the making of Laura, Preminger’s 1944 film noir masterpiece. “Freedom of choice was in rather short supply at 20th Century Fox under Zanuck,” he recalls. “I was turning out a string of films following rules and obeying orders, not unlike a foreman in a sausage factory.” His frustration is still vivid after so many years. And easily understandable. “I was reduced almost to a puppet. I was not able to cast without interference. When the picture was finished, I was denied final cut.” Never giving up, he tried hard to constantly fight “the absurd censorship and puritan morality” which at the time was imposed upon Hollywood films.No wonder that after a few years he no longer wanted to be under contract with a studio.

As one might expect, the book is filled with many interesting anecdotes, often told with a deadpan irony and a slightly sarcastic tone. Never holding back about his feuds, naming enemies, or exalting his friends, remembering what he calls, “my days of failure as well as my days of success.” Not so much thought about his famous temper and his well-known penchant for autocratic behavior on set. He gives inside glimpses on the making of some of his films and the numerous stars he worked with. Joan Crawford (Daisy Kenyon) was “a competent, remarkable and very generous woman.” Gary Cooper (The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell) “a great film star on screen and in life a charming, witty, intelligent and entertaining companion.” How Marilyn Monroe whose “off-camera personality was very different from what she represented on the screen, was vulnerable and craved nothing more than affection. Her ambition was to become a great dramatic actress and she underrated her natural magic in front of the camera.” He tells how he had to endure the toxic influence of her coach during the location filming of River of No Return.

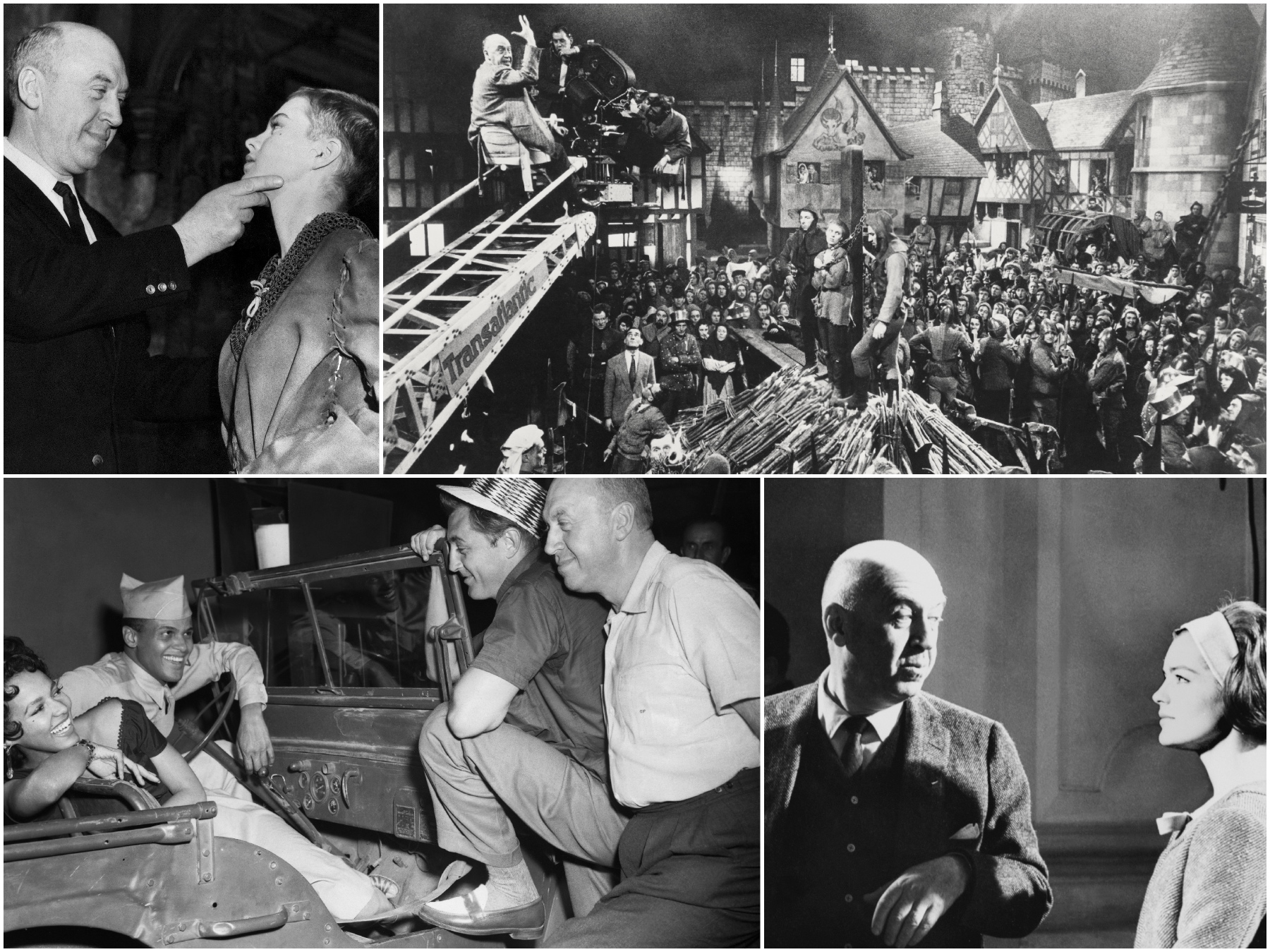

Scenes from an Otto-biography: with the ‘inexperienced’ Jean Seberg; directing the climatic scene of St. Joan, 1957; with Romy Schneider on the set of The Cardinal, 1963; with Robert Mitchum, Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge on the set of Carmen Jones, 1954.

gamma-rapho/bettman/corbis historical/getty images

Preminger takes sole responsibility for the failure of Saint Joan with the inexperienced (his word) Jean Seberg that he had discovered aged 17 after 18000 hopefuls had auditioned for the part in a well-publicized worldwide search. (He confesses that Barbra Streisand was one of them). “I am alone to blame.” John Wayne (In Harm’s Way) was “an ideal professional, always prompt and prepared, also humorous”. John Huston, whom he cast in the Golden Globe-winning The Cardinal in 1963, “was a joy to direct. He behaved as we both want actors to behave: he came to the set on time knowing his lines. He rehearsed and did his part without the slightest critical comment about the director or even a hint of professional advice. Perfect.” On Jean Simmons for Angel Face, he simply writes, never mentioning her name, that “The actress was most cooperative. I enjoyed working with her.” Paul Newman gets the same expedited treatment, only referred to because Preminger managed to cut his salary in half for Exodus, his 1960 epic film about the birth of Israel. And the two were barely on speaking terms during the filming!

The filmmaker takes pride in breaking the color barrier as early as 1954 with the all-black casting of Carmen Jones and five years later with Porgy and Bess – both of them starring Dorothy Dandridge, with whom he had a long and complicated affair. Reading the book you wouldn’t know it, even though he mentions numerous other dalliances, notably with Gypsy Rose Lee. He proudly elaborates on the blacklisting during the 1950s, how he hired Dalton Trumbo to write the script of Exodus. “I told him I was going to break the boycott against him and give him screen credit under his real name for the first time in fifteen years. He didn’t believe it could be done but I succeeded and the days of the blacklist were finally over.”

For some reason, while filming The Man with a Golden Arm, Frank Sinatra called him Ludvig and in return, Preminger always addressed him as Anatole! “He was compassionate about Kim Novak’s extreme nervousness in front of the camera. She was terrified and though she tried very hard she had great difficulties delivering her lines believably. Sometimes we even had to do very short scenes as often as 35 times. But Sinatra never complained and never made her feel that he was losing patience.” Later Paramount offered The Godfather to Preminger. “I thought Sinatra would be wonderful in it and I sent him the book. But he passed on it and me too as I did not want to do the film without him.”

He regrets that in 1961 Martin Luther King turned down an offer to play a senator from Georgia in Advise and Consent. “I wanted to demonstrate that a black man could creditable in such a political situation. He was intrigued but at the last moment, he declined. He decided that the hostility his presence would create in that role would jeopardize his cause.” He salutes the work of some of his brilliant cinematographers, Joseph LaShelle, Sam Leavitt, Leon Shamroy. Saul Bass also is acknowledged for designing some of the most groundbreaking opening credits of his pictures, and actually the jacket of this book with the front cover showing the back of his bald head. His face is on the back cover! He thanks the composers David Raksin, Elmer Bernstein, Ernest Gold, Jerry Goldsmith, Duke Ellington, Dimitri Tiomkin, all of whom contributed to memorable and haunting scores…

At the time he finished his… Otto-biography, Preminger was 72 and his last film, Rosebud, had been released two years earlier. He would direct only one more movie, The Human Factor, in 1979, before his death in 1986. Leaving an important legacy in American cinema…and the lasting image of an eclectic and stylish director who often, as he insists “always refused to play safe.”