- Festivals

Living in a Fragile World: the Impermanent Lives of Migrants and Refugees Reach Cannes

With the first weekend looming, Cannes is indeed in full swing and traffic on the Croisette, compounded by checkpoints, sold-out café patios and bumper to bumper black sedans is reaching the customary frenzy. Alongside the main competitions the sidebars – Quinzaine and Semaine de la Critique – have also begun screenings. And faithful to tradition they contain some pleasant surprises.

In Southern Italian Romani parlance a “ciambra” denotes a clan, and Italian American director Jonas Carpignano’s A Ciambra brought an entire such family to Cannes and to the thunderous applause of the Directors Fortnight audience. The young Italian American director is not a novice at the festival, having previously participated in the Semaine de La Critique section. “Graduating” this time to the Quinzaine, he showed a film steeped in the Italian neorealist tradition as well as modern documentary influenced dramas (think last year’s American Honey or Matteo Garrone’e Gomorra).

Carpignano, who resides in Gioia Tauro, the small port city in Calabria infamous for the local influence of the ‘Ndragheta organized crime syndicate, previously produced a short about the family of Gypsies he first met when they stole his car in 2011. As he explained from the Quinzaine stage, he became fascinated with the real-life Amato family and the squalid compound the clan calls home. “I knew then this was a reality that needed to be expressed on a movie screen,” the director added. Among those who agreed was Martin Scorsese, who executive-produced the film.

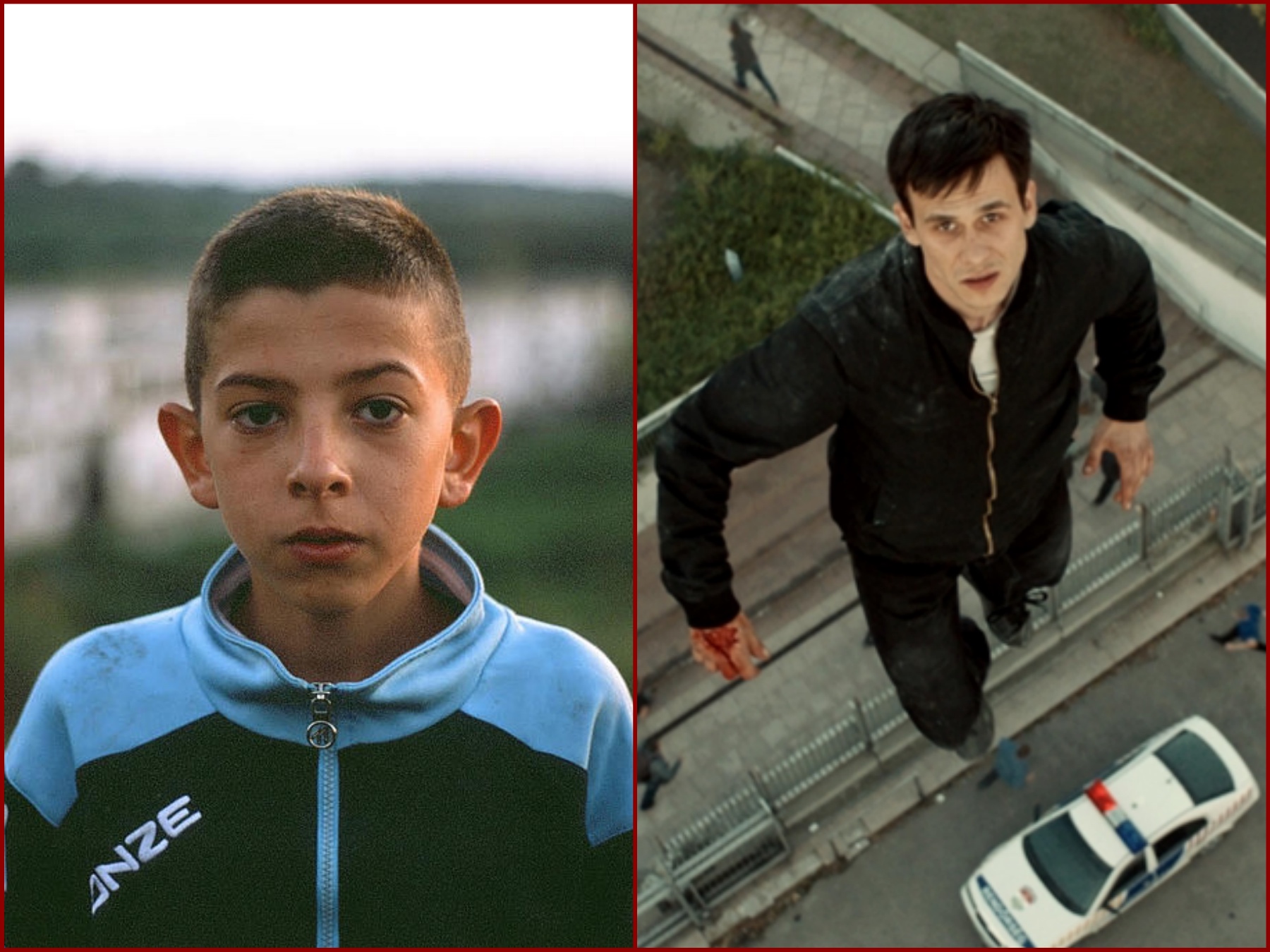

The story centers on fifteen-year old Pio, on the cusp of coming of age and graduating to the life of small-time theft through which the men support the family. Even as he chafes to become a full-fledged adult member of the clan, his father, mother and older brothers – constantly in and out of prison – rebuff his demands for full participation. Pio, playing himself –a brooding, magnetic presence for a non-professional actor – channels his frustration through a warm friendship with a good natured immigrant from Burkina Faso (Koudos Seihon) who becomes a surrogate parent of sorts, helping him but also steering him away form the life of petty crime and especially the more dangerous liaisons with the menacing organized crime of “the Italians” which looms in the background.

It’s a slice- of-life , coming-of age story which s truly remarkable for the legitimacy of having the ultimate outsiders – a Romani family – tell their own story which is in turn painful, emotional and elegiac. The Amato family is remarkable as cast – from grandparents to toddlers, and Pio is a standout. It is also an empathetic portrayal of a region, at the tip of the Italian boot which is a crossroads of the contemporary issues that plague and define modern society: poverty, discrimination, race and crime. It is sometimes difficult to remember that this landscape of organized crime, illegal immigrant labor, refugees and endemic unlawfulness is in fact Europe and not what we think of as the distant “developing world”.

Europe and the crisis it faces are also the backdrop for another film in competition: Jupiter’s Moon. Hungarian director Kornél Munruczó previously screened Johanna in Un Certain Regard 2005 and his White God won the main prize for that section in 2014.. This year’s Jupiter’s Moon is a magic realist parable steeped in the current, dramatic refugee crisis sweeping Europe. (In the preamble we are reminded that of Jupiter’s many moons, one has an ice-covered ocean deemed capable of sustaining life and it has been named Europa). The rest of the film seems to question whether that is a quality which remains part of the old continent and, as it faces a refugees crisis of staggering proportions, it is capable of sustaining them and, not least, preserving its own humanity.

The film starts with a scene of immigrant-smuggling as harrowing as any staged on the Rio Grande. In the perilous crossing a group of Syrian refugees runs into the Hungarian border patrol. Aryan (Zsombor Jéger),fleeing war-torn Homs, is shot by a policeman and soon after collapsing to the ground he mysteriously levitates. His newfound capacity for floating in the air apparently heals him and astonishes Dr. Stern (Merab Nindze) who treats him in the refugee camp where the desperate immigrants await deportation. Recovering from the initial surprise, the doctor – who has incurred a large debt due to malpractice – convinces Aryan to join forces and use his newfound powers strategically to raise the funds each man needs to make their lives right. Breaking Aryan out of the camp sets up a cat and mouse pursuit between them and László (György Cserhalmi) something of a “bad detective” or at least the Magyar version of a morally (and actually) corrupt cop. The chase winds through a beautifully filmed and suggestively run-down Budapest, fairly exuding imperial downfall and the above mentioned moral decay.

The angelic refugee ascending to the heavens is a an interestingly transcendental take on a very terrestrial issue and Munruczó shoots some truly memorable scenes even while, as many critics here remarked, he is not quite able to convincingly close his ambitious narrative and metaphorical deal. One thing is certain, once again the theme of migration reverberate though the festival as they percolate, especially through European cinema.