- Film

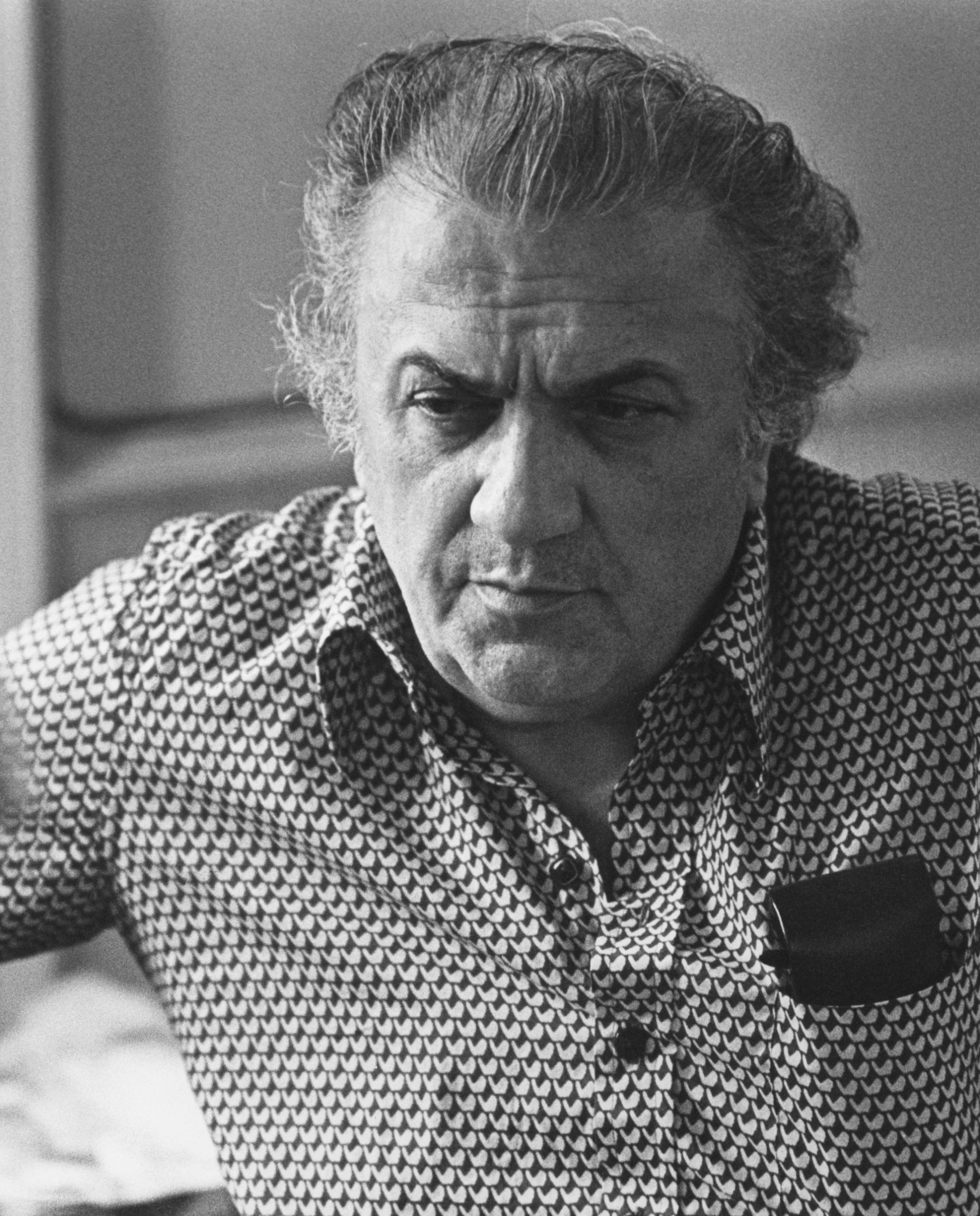

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Fellini on Fellini

What better way to celebrate Federico Fellini’s centennial than reading the appropriately titled “Fellini on Fellini”? Not an autobiography per se, and initially published in 1974, a year after the release of the seminal Amarcord, this slim volume is a random selection of his articles, essays, letters, introspective musings and miscellanies on many topics dating back to 1955. A perfect complement for a different insight into the persona and work of a legendary filmmaker that has been so obsessively analyzed, documented, and scrutinized over the years.

“I am a liar, but an honest one,” the Maestro amusingly warns at some point. One of the thought-provoking axioms that abound in these pages.

The book opens with a lengthy love letter to his hometown of Rimini, on the Adriatic coast, where he was born and which he had left at age 17 in 1937. As he reluctantly returns for a pilgrimage exactly 30 years later, he is confronted by a place he can barely recognize. The familiar landscape of his childhood eradicated, the city of his youth is now invaded by tourists and disfigured by towering hotels, dance halls, souvenir shops, open-air markets, and enormous department stores.

Roaming around town, on the Corso and the seafront promenade, he “felt foreign, defrauded, diminished.” He nostalgically remembers the winter mist on the windswept empty beaches, the many pranks done with his friends. If their old haunts, the Café Commercio, the Fulgor cinema, and the Grand Hotel, are still standing, he finds that “all had suddenly become gigantic as if grown without my permission, without asking my advice.” He is overcome by a maelstrom of emotions that leave him puzzled “by the new form my home town had taken on, all this unknown Rimini, this strange place that appeared to me to be Las Vegas, that seemed to be trying to tell me, that it had changed, and that I had better change as well.”

Federico Fellini (R) and his brother Riccardo on the beach at Rimini, Italy, 1920s.

Time Life Pictures/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

This bygone era was the setting and the inspiration for his third feature I Vitelloni (1953) and would later serve as the narrative thread in Amarcord. Even if he feels that Rimini now, “is a dimension of my memory, nothing more.”

In a text dated 1961, he evokes the determining meeting with Roberto Rossellini and his collaboration on the scripts of Rome, Open City in 1945, and then on Paisá. The latter, he considered “his first real contact with cinema. From this, I learned that it was perhaps the medium of expression most congenial to me. I felt that the cinema was the right form of expression for me. I understood that to be a director and to make films could fill my life. I couldn’t ask for anything more; it could become so enriching, so fascinating, so moving – a thing that justifies you and helps you find a meaning…”

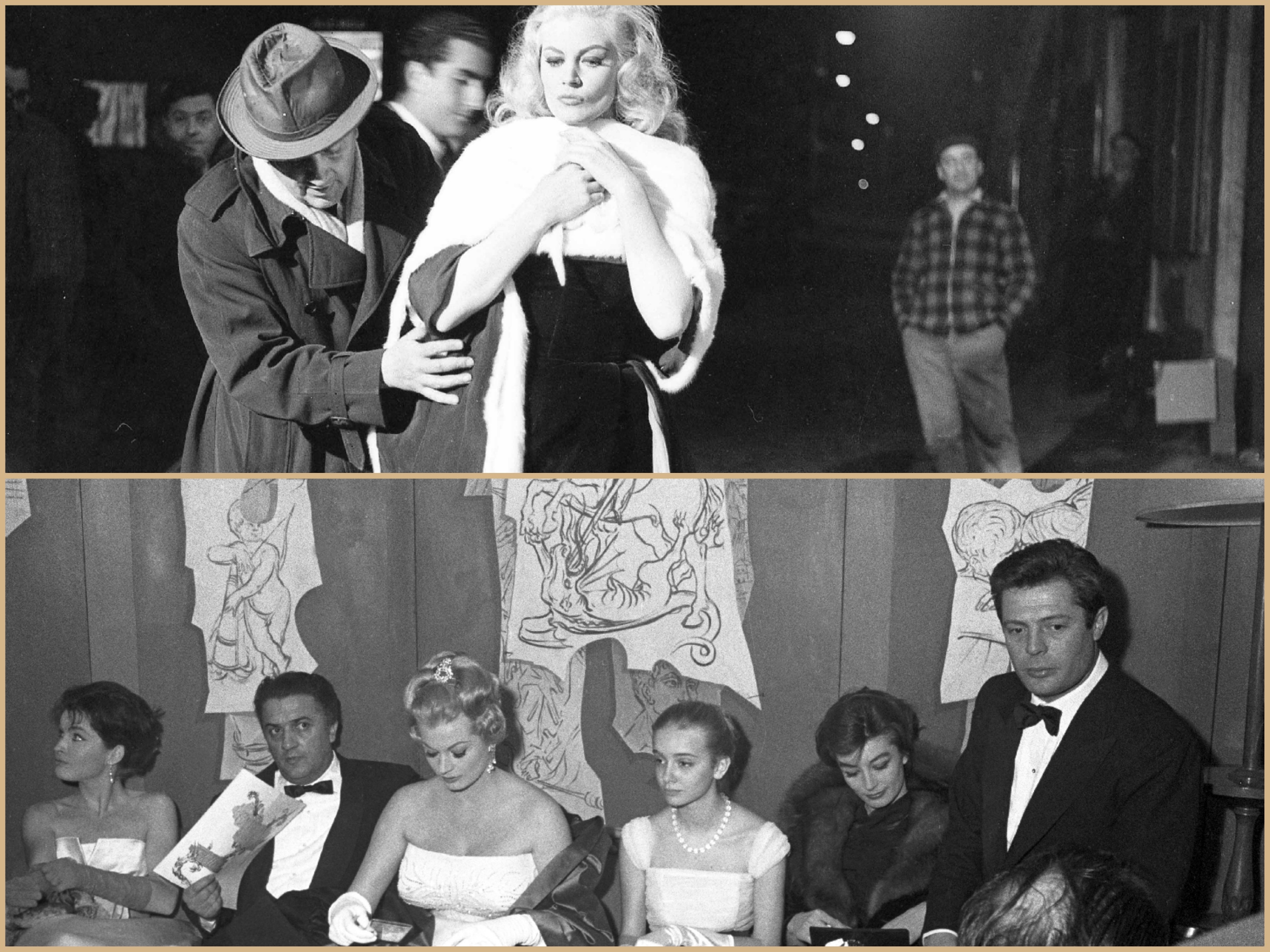

Equally revealing is an article on La Dolce Vita written in 1962, two years after the release of the film, and published in Issue 27 of the weekly magazine L’Europeo. Today, all has been said on the inception and making of his groundbreaking opus. But it is nonetheless worth looking back at how Fellini dealt with the aftermath of its success at the time. “Let me say straight off, I never go to Via Veneto,” he confesses, alluding to the world-famous street in Rome, forever synonymous with the mythical and decadent way of life depicted in the picture.

It was there, at the Café de Paris, that he once saw Farouk, the ex-King of Egypt, throwing a fit after being provoked by aggressive photographers, there that he spent many summer evenings chatting with the paparazzo Tazio Secchiaroli whose stories inspired him and would help shape Marcello Mastroianni’s iconic character.

There also that he shot several memorable scenes before too much chaos would force him to recreate a large stretch of it at Cinecittà Studios where filming took place on Stage 5. He recounts how many foreign journalists, especially Americans, beg him to give them a private tour along Via Veneto and, if possible, to bring Anita Ekberg along! “When I say that I can do nothing, no one believes me. People would believe me even less if I were, to tell the truth: and that is in my film I invented a non-existent Via Veneto, enlarging and altering it with poetic license until it took on the dimension of a large allegorical fresco.”

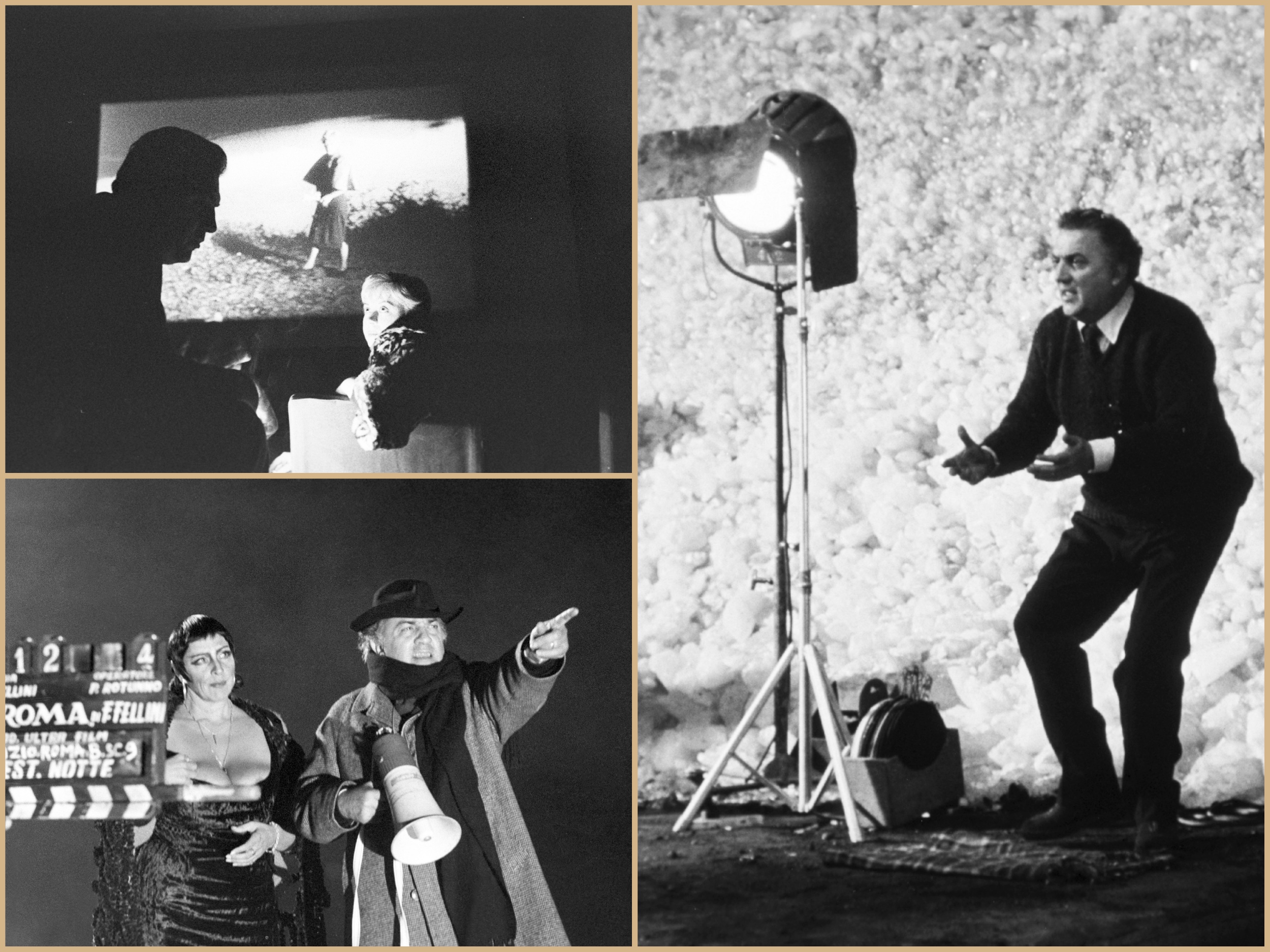

Cinecittà – another place forever linked to his name as he shot most of his films in its soundstages. “I have spent the happiest part of my working life there. It’s my factory.”

(Left, top) With Giulietta Masina watching the rushes for Nights of Cabiria, 1957; (left, bottom) on the set of Roma, 1972; (right) directing Satyricon at the Cinecittá, 1969.

Jack Garofalo/Paris Match via Getty Images/Pierluigi Praturlon/Reporters Associati & Archivi/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images

In “The Birth a Film,” based on a conversation with Enzo Siciliano published in the newsmagazine Il Mondo in 1973 while promoting Amarcord, Fellini describes his creative process and how he invents his filmmaking grammar. It starts simply with a vision, a feeling. At this stage, “it cannot be described in words,” he explains, “because it would become a kind of materialization that has nothing to do with the film itself. When I am preparing, I write very little. I prefer to draw the characters and the sets. Words are seductive but they flatten out the precise dimensions, the merely visual demands of the film.” Then comes another phase, the most fascinating for him – ‘when it exists in flashes in bits and pieces, where all is still malleable and opened to endless possibilities until suddenly filming has to begin’ and he has to submit himself to the constraints of the shooting schedule. On the set, he has “no need for an atmosphere of discipline and silence. I like people to come and see me, and I can indulge my taste for clowning.”

Chapter after chapter, we follow Fellini’s vivid recollections recounted from a somewhat haphazard and fragmentary perspective, providing a kaleidoscopic potpourri highly revealing of his effervescent creative mind. Often prone to provocative statements, he asserts for instance, maybe jokingly, or not, that the movie business is “grotesque. A combination of a soccer game and a brothel.” Another surprising statement? “It is impertinent to call my films autobiographical,” he claims. “I have invented my own life. I have invented it specifically for the screen. I lived to discover and create a film director. And I can remember nothing else, although I am thought to be a man whose whole expressive life is spent in the great department stores of memory.”

There is a moving special tribute to his wife Giulietta Masina, whom he married in 1943 and who starred in seven of his films, and “her gift for evoking a kind of waking dream quite spontaneously, as if it were taking place quite outside her own consciousness. With her clown-like gift for mimicry, she embodies in our relationship my nostalgia for innocence.” With Marcello Mastroianni, he confesses to having “a deep sense of our working together. He is a friend, someone I know well. The way he really helps me is not just being professionally good, but by abandoning himself confidently to me, which means that I can take risks…It is another sort of cooperation.”

He explains why composer Nino Rota has been his preferred choice when it comes to scoring his films, the result of a deep connection started on The White Sheik in 1952.

(Top) Directing Anita Ekberg during the shoting of La Dolce Vita, Rome, 1969; (bottom) with Marcello Mastroianni, Anita Ekberg and Anouk Aimée at the premiere of the La Dolce Vita at the cinema Fiamma in Rome, 3rd January 1960

Archivio Cicconi/Getty Images

He affirms having no regret turning down offers to make sequels to I Vitelloni, The Nights of Cabiria and La Strada. On the latter, he explains that producers “did not realize I had already said all I wanted to say about Gelsomina. I could have made a fortune selling her name to doll manufacturers. Even Disney wanted to make an animated cartoon about her. I could have lived on Gelsomina for twenty years.”

One might regret that this compilation does not include anything about 8 ½, Juliet of the Spirits, Satyricon, Casanova, or Roma, even though a large section is devoted to The Clowns.

But it stops in 1973, and only deals with the first part of a career that would go on for twenty more years, during which he made seven more films, until his death in 1993, at age 73.

In the end, one is impressed by Fellini’s modest sense of awe when trying to translate what cinema means to him. “I know the unreality of it all: its limitations, the feeling of exaltation and extravagance which it brings, the dangerous romantic risks, but outside of cinema I know no other way in which I can feel at ease, and in tune with my own self.”