- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Jean Renoir, “My Life And My Films’

In “My Life And My Films” published in 1974, five years before his death in Beverly Hills at 84, Jean Renoir takes the reader through his rich existence, starting from his early childhood. As the son of the illustrious painter, he knew he had to make a name for himself in whatever field he chose. “But,” he admits in retrospect, “I spent my life trying to determine the extent of the influence of my father upon me, passing from periods when I did my utmost to escape from it to dwell upon those when my mind was filled with the precepts I thought I had gleaned from him. When I started to make films, I went out of my way to repudiate my father’s principle, but, strangely, it is in the productions where I thought I avoided Renoir’s aesthetics that his influence is the most apparent.” That would be reflected in a lengthy career spanning 45 years during which he made 39 films.

Renoir père – the acclaimed painter – advised him to try ceramics, but it turned out to be a short-lived occupation. Convalescing after being wounded at the beginning of the war in 1914, Jean discovered American films. He was blown away by Charlie Chaplin and “the genius of The Tramp.”

In 1920, he married Catherine Hessling who had been his father’s latest model. “I must insist on the fact that I set foot in the world of cinema only in order to make my wife a star. I did not foresee that once I had been caught in the machinery, I should never be able to escape.” By 1924, “the bug of film directing had now taken root in me and there was no resisting it.” He would direct her in five silent films, often experimenting with improvisation, technical tricks, sharp contrasts, and displaying an obsession for close-ups. “An example of the insecurity of my convictions,” he writes. “At the beginning of my career, I was only interested in artificiality.”

In order to finance his movies, none of them making any profit, he had to sell many of the paintings inherited from his father after his death in 1919, keeping only the empty frames. Running out of money and faced with mounting debts but wanting to hold on to the remaining few artworks in his possession, he thought of giving up moviemaking altogether for good. “At the risk of sounding sordid, “he confesses, “ I cannot refrain from dividing my career in two purely material halves, during the first of which I paid to make films, whereas in the second I was paid to make to do so.”

The arrival of sound in 1929 gave him an unexpected boost. He rejoiced at being able to experiment again with a new medium. He transitioned with ease to the talkies and the thirties were a prolific period with many humanist dramas often infused with the poetic realism and raw naturalism that sealed his reputation. Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), A Day in the Country (1936), La Grande Illusion (1937), The Human Beast (1938) The Rules of the Game (1939). Now considered his masterpiece and a classic, the latter was not well received and even banned after a few months for “being depressing, morbid, immoral and having an undesirable influence over the young.”

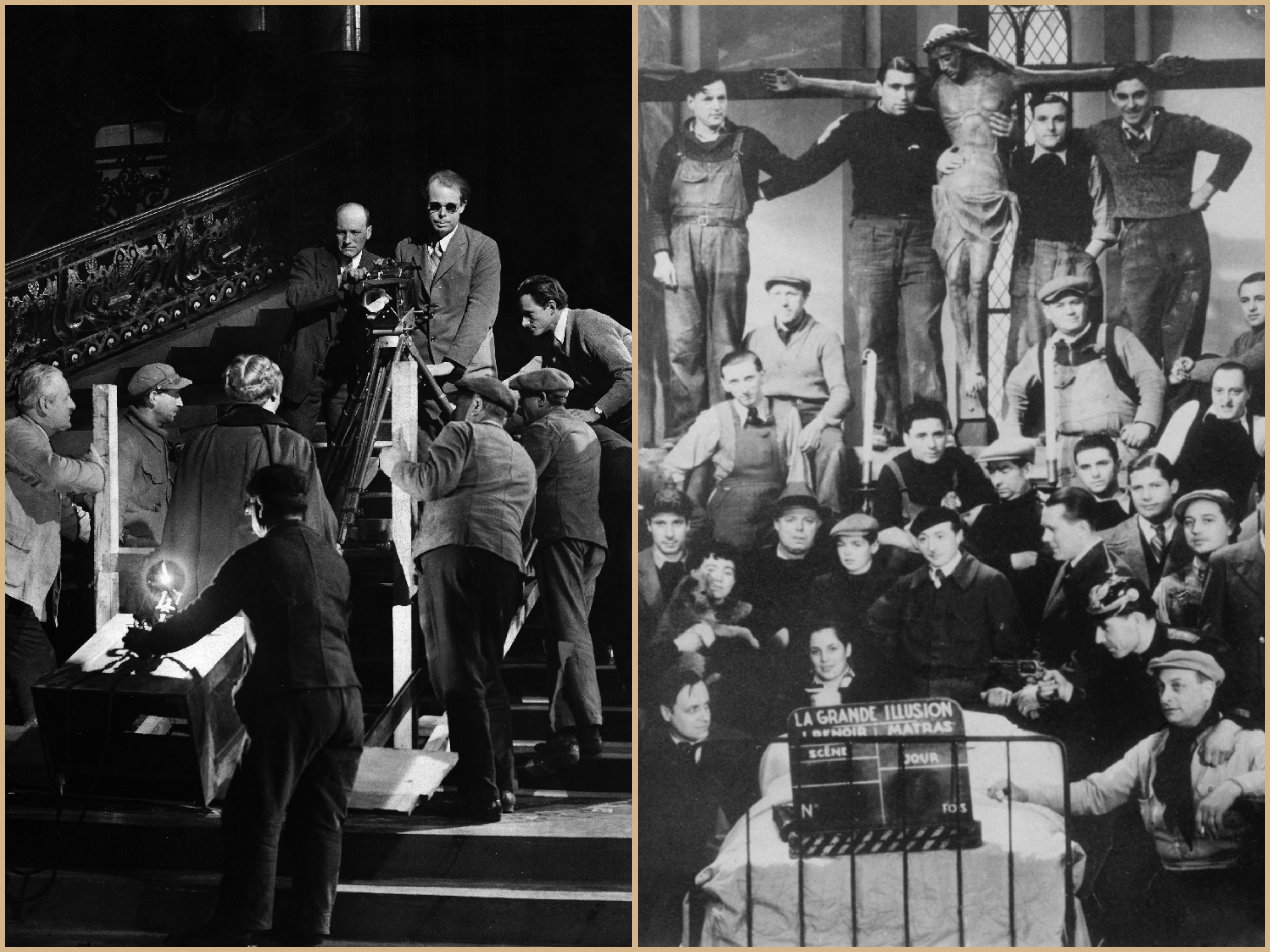

InIn 1926, setting up a shot (with glasses, behind the camera); with the crew of La Grande Illusion, in 1937 – first row behind the bed, left, with a hat, next to a boy.

ullstein bild via Getty Images/Micheline PELLETIER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

A crushed Renoir admits that “the failure of La Règle du Jeu so depressed me that I resolved to give up cinema or leave France.” With the country at war a year later, his friend Robert Flaherty urged him to move to America. And he did.

On his flight to Hollywood in early January 1941, he could not help dreaming of “settling in that paradise, with Griffith, Chaplin, Lubitsch, and all the other great figures of the cult of the cinema.” He would later meet D.W.Griffith, “but, by then the visionary who had created a new art-form was a bitter man.”

Even if he felt welcomed with open arms by Twentieth Century Fox, reality soon set in: “I was quick to realize that what the studio expected of me was not that I should bring my own methods but that I would adopt those of Hollywood. I argued endlessly with Darryl Zanuck who proposed to get me to film French stories, which was the very last thing I wanted.” He finally succeeded in letting him try instead a purely American one, Swamp Water, written by Dudley Nichols, and to film all the exteriors on location in Georgia. It was a hard sell. No one understood why he would not use the convenience of the studio back-lot. “My problem in Hollywood was always the same, that the job I’m trying to achieve has nothing to do with the purely industrial side of film. I have never been able to see cinema only on those terms.” Still, he managed to make four other movies.

But in 1947, the fiasco of The Woman on the Beach, a film noir starring Joan Bennett and Robert Ryan under the RKO banner, was another blow. “It was the end of my Hollywood adventure. I never made another movie for an American studio.” He never forgot Zanuck’s crushing remark: “Renoir is very talented, but he is not one of us.”

His next independent project was not easy to finance but proved to be one of his most rewarding and professionally energizing. The discovery of India where he spent several months in 1950 for his first film in color, The River. An adaptation of Rumer Godden’s novel published in 1946 about an English family in Bengal, “a tender and simple tale dealing with the immemorial themes of childhood, love, and death.” For the pivotal part of the captain who had lost a leg and cannot resign himself to his physical disability, Renoir met with Marlon Brando. “But he was reaching the heights of his powers and his very presence would have transformed the film, so with regret, I dispensed with that great actor.” In 2005, the film was restored in its all-glorious Technicolor with the help of the Film Foundation and the HFPA.

Clockwise from top left: with Anna Magnani on the set of The Golden Coach, 1952; instructing Ingrid Bergman during the shooting of Elena and Her Men, with Jean Claudio (L) and film music compositor Joseph Kosma, in 1955; in a Paris restaurant with Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer, in October of 1955.

Mondadori via Getty Images/AFP via Getty Images/Keystone/Getty Images

In 1952, he was back in France. “We returned after a few years to the scenes of our youth and find we cannot recognize them. That is why, for our peace of mind, we must try to escape from the spell of memories. Our salvation lies in plunging resolutely into the hell of the new world, a world horizontally divided, a world without passion or nostalgia.”

In Italy, he made The Golden Coach with the volcanic Anna Magnani. Followed by Elena And Her Men with Ingrid Bergman and French Cancan which reunited him with Jean Gabin. All were filmed entirely in studio. Unlike the 1959 Picnic on the Grass which he shot at Les Collettes, near Cagnes-sur-Mer, on the Riviera, the farmhouse his father had bought in 1907. “I had the immense pleasure of filming the olive trees my dad had so often painted. That movie was like a bath of purity and optimism.” In a reflective mood, he confesses that if he spent his life experimenting with different styles, it was always “to arrive at the inward truth, which for me is the only one that matters.”

After that European interlude, he settled back permanently to his Beverly Hills house on Leona Drive. To the surprise of many who wondered why (even though he had been an American citizen since 1946), he would respond. “My answer is that the environment which has made me what I am is the cinema. I am a citizen of the world of films.”

After his death, Orson Welles called Jean Renoir “the greatest of all directors.’