- Festivals

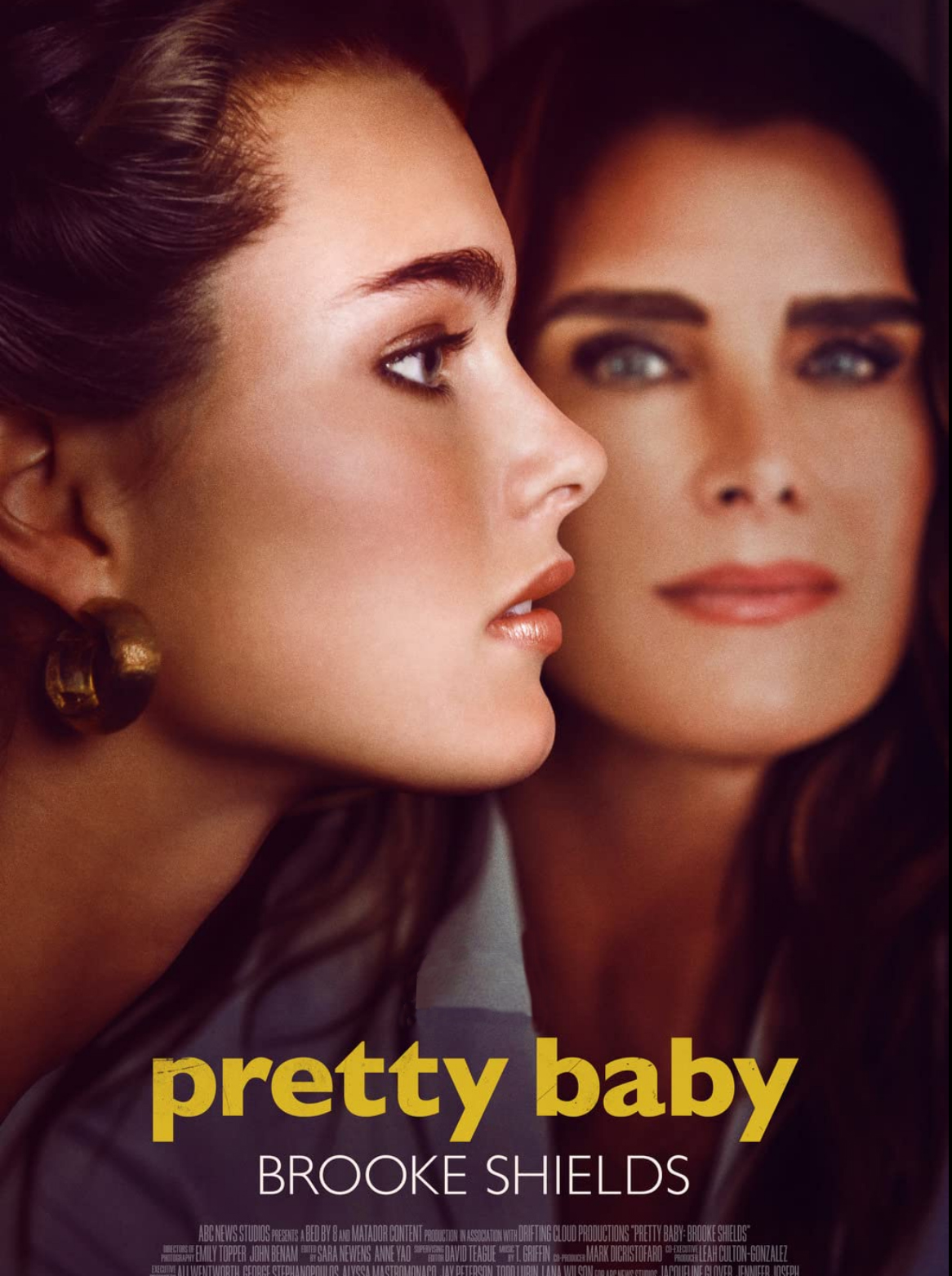

Sundance 2023: Docs – “Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields” Unpacks Uncomfortable Objectification of Its Subject

The rise of social media has created the opportunity for people to connect with those who might have suffered trauma similar to their own. In parallel, it has also helped provide a vocally receptive audience to a trend in the nonfiction film space — a broader reexamination of the past treatment, both by the media and society at large, of female public figures, especially actresses, singers, and other celebrities.

The latest documentary of this type, sure to receive a warm public reception, comes in the form of a look at Brooke Shields, the child model and actress whose ubiquity in the late 1970s through the mid-’80s came hitched to a string of controversial projects that sexualized her. All before she was 16 years old.

While characterized by a fair amount of repetitive churn, as well as a bit of frustrating avoidance, the two-part Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields serves as a disquieting portrait of adolescent sexualization. It also asks a crucial question: if someone is presented constantly and almost exclusively as the object of others’ desire, what does that do to their self-image, and ability to form healthy and functional relationships?

Shields got her start in show business as a baby. Mother Teri and sales executive father Frank divorced when Brooke was only five months old. It was Teri who pushed the beautiful girl into commercials.

The first part of the movie, which enjoyed its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival, charts both this upbringing and Shields’s professional life up through her enrollment at Princeton University. In the process, it serves as a slam-dunk condemnation of the broader cultural misogyny of the era.

At 12, Shields starred in Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby, as the underage daughter of a New Orleans brothel worker who herself becomes a prostitute. High-profile lead roles followed in hormonally charged coming-of-age romances The Blue Lagoon and Endless Love, plus a provocative ad campaign for Calvin Klein jeans. While not without controversy at the time (“Brooke is 12. She poses nude. Teri is her mother. She thinks it’s swell,” read the cover of a September 1977 New York Magazine story), this material will no doubt land as especially jaw-dropping for viewers unfamiliar with its history.

The documentary’s second portion, while touching upon professional rebirth with the sitcom Suddenly Susan, leans much more into its subject’s personal relationships (Michael Jackson, Dean Cain, Andre Agassi, and second husband Chris Henchy), as well as postpartum depression (and, yes, that famous spat with Tom Cruise) after the birth of her first daughter. In wrenching fashion, Shields also details a sexual assault she experienced in her early 20s, just as she was attempting to make a comeback in Hollywood after graduating from college.

Emmy Award-winning director Lana Wilson, whose work includes After Tiller and the 2020 Sundance opening night film Miss Americana, does a good job of crafting a vehicle that allows Shields to speak her truth, while also situating it within society at large. Set to debut later this year on Hulu, Wilson’s movie very much works as a sermon to the choir. Alternating archival clips and photos with a lot of new interview footage, this work illuminates Shields’s story as an inspiring one for an audience who remembers much of it while also providing enough of a primer to connect with younger viewers.

Part of the tradeoff, however, seems to be an acquiescence to leave certain questions unasked or, at least, unpressed — to accept a framing of Shields’s life that, while not false, is also politely reductive. A fair number of blanks are left unfilled.

When it comes to her father’s thoughts on her work, it’s Shields’s stepsister who provides answers, saying that he “wasn’t really into show business.” When addressing her mother’s alcoholism, it’s childhood friend Laura Linney who has many more reflections to offer, recounting hiding behind locked doors and waiting for the quiet which was a signal that it was safe for them to come out.

Does this mean Teri was abusive, either verbally or physically, or simply loud and frightening? Was there something in her childhood that in turn led Teri to actively steer her daughter toward work that, to put it mildly, most parents would have qualms about? Did Shields’s deeply conservative father have no input or say in her work life? Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields mostly avoids these questions.

The result is psychologically self-protective, no doubt. But this myopic, make-nice instinct on Wilson’s part also feels a bit like a missed opportunity, a golf putt left just a few inches from the hole.

Shields, now 57, is by all accounts well-adjusted. Near its conclusion, one of the movie’s most heartwarming scenes finds her engaged in candid dinner table conversation with her two daughters, exchanging perspectives on the nudity and overt sexualization of her early filmography. This sequence leaves viewers in a settled place, exhilarated for her health and happiness on a personal level and hopeful about intergenerational dialogues that might shape a world that better respects and protects childhood innocence.

With just a little deeper digging, though, it feels like Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields could have spoken an even more difficult truth capable of sparking further personal introspection and, perhaps, substantial change among those not afforded the same level of resources in care as Shields.