- Industry

Out of the Vaults: The Man with the Golden Arm (1955)

When director Otto Preminger bought the rights to make The Man with the Golden Arm, he knew he would have problems with the Production Code Administration: he knew they would refuse to grant him a Code seal to release the movie. The film dealt with drug abuse, a subject that was censored, along with miscegenation, prostitution, abortion, and words like “virgin” and “pregnant.” Undeterred, Preminger started production on the picture, vowing to release it without the seal if he had to. United Artists, the studio backing the film with a million-dollar investment, was behind him, despite the certainty of a $25,000 fine from the MPAA, and despite the fact that Preminger had given it an out if the seal was denied. UA resigned from the MPAA (it rejoined later) and released the film through the many cinemas that were willing to book it. Following the controversy that ensued, there was an investigation of the PCA’s Code approval process, and the 25-year-old Code was overhauled for the first time since its adoption in 1930.

The Man with the Golden Arm finally received a seal in 1961 and Preminger, to whom the rights had reverted, sold the television rights to ABC, who were contractually bound not to cut the film. Preminger even got to decide where the commercial breaks would be inserted.

The film was based on Nelson Algren’s 1949 bestselling book of the same name, the first to win a National Book Award. Algren sold the film rights to UA, was hired and then fired as the film’s screenwriter, and later disavowed the film, saying that it bore little resemblance to the story he wrote.

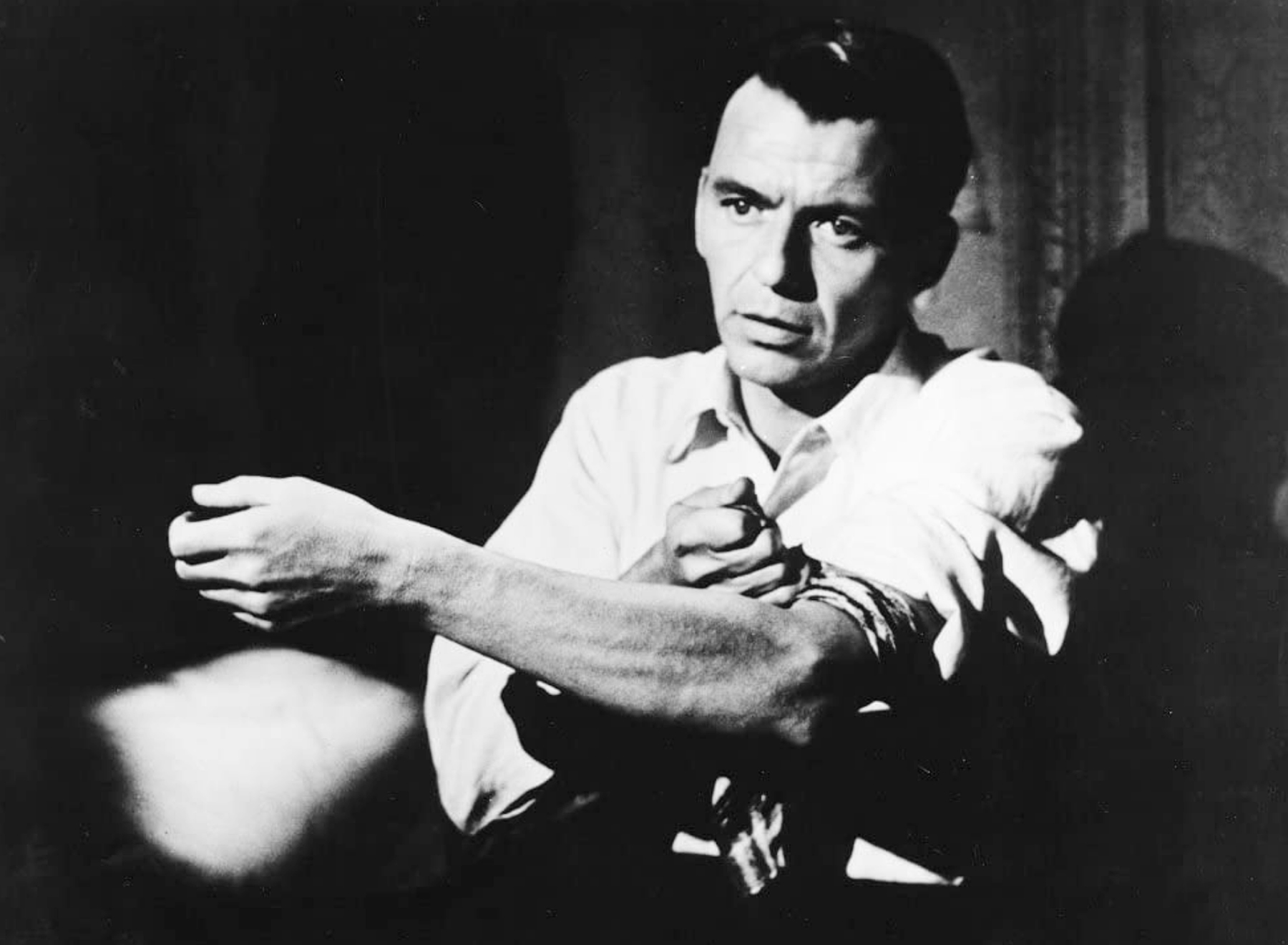

In the film, Frank Sinatra plays Frankie Machine, a poker dealer (the man with the golden arm), who has just been released from prison. He has kicked his drug habit thanks to the prison doctors and now wants to give up gambling and become a musician. He returns to his life in Chicago and to his wife Zosh (Eleanor Parker, borrowed from MGM), a malingering invalid in a wheelchair who wants things to go back the way they were, and repeatedly thwarts his dream of playing in a band. Slowly, Frankie finds himself sucked into his old bad habits, despite the best efforts of his girlfriend, played by Kim Novak, borrowed from Columbia. (Columbia was paid $100,000 for her; she made $1,000 a week.) Robert Strauss plays Schweifka, the poker boss who lures Frankie back with the promise of money for his sick wife; Darren McGavin plays his ruthless pusher Louie.

Sinatra turns in a fine performance as the addicted Frankie; his natural charm makes a weak character seem sympathetic as he struggles through his recidivism and his eventual attempt to “kick the monkey.” The star spent time at drug rehabilitation facilities studying inmates in order to inform his performance. Most of the cast is equally strong, particularly McGavin as Louie – he’s seen it all in his jaded life, and he knows before Frankie does, that all it will take is the offer of a free fix for Frankie to fall. Equally good is Arnold Stang as the dimwitted sneak thief Sparrow, faithful to his friend Frankie until Frankie has no time for him anymore. The one performance that is below par is that of Parker, playing Zosh in a hyper, borderline hysterical way, indicating her character rather than performing in a truthful way.

Preminger was widely known as a bullying director, hectoring his actors and routinely humiliating them, famous for quotes like “I do not welcome advice from actors, they are here to act,” and “Marilyn Monroe? A vacuum with nipples.” However, he did guide nine actors (including Sinatra) to Oscar-nominated performances and had a successful career in Hollywood despite his difficult reputation.

When both Sinatra and Brando were offered the role of Frankie, Sinatra swooped in and commandeered it, smarting from the fact that he had lost On the Waterfront to his rival. His instincts were right, and he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor. The film also got nominations for art direction for Joseph C. Wright and Darrell Silvera, and for the score for Elmer Bernstein.

The distinctive crooked arm on the poster and publicity materials for the movie, designed by Saul Bass, is considered a tour de force of movie marketing and was listed by Premiere magazine as one of ‘The 25 Best Movie Posters Ever. In the paper-cut animation on the title credits, white bars appear and disappear against a black background accompanied by Bernstein’s score, ending with the same disjointed hand, meant to convey the grimness of the subject with the lightest of touches.

The jazz score, composed by then 33-year-old Elmer Bernstein, is another triumph. Bernstein hired drummer Shelly Manne, Shorty Rogers and Pete Candoli on trumpets, Milt Bernhart on trombone and Bud Shank on alto saxophone, all musician virtuosos to do the solos: he had been given three weeks to compose the score, and never saw the opening credits ahead of time as Bass was working on them simultaneously. “The intent of this opening was to create a mood spare, gaunt, with a driving intensity… [to convey] the distortion and jaggedness, the disconnectedness and disjointedness of the addict’s life the subject of the film,” Bass said at the time, and Bernstein, with his drums, horn, and trumpet, reflects the feeling musically in the accompanying cut Clarke Street as the credits end and Frankie steps off the bus into his life on that street. (It was Manne who taught Sinatra to play drums in the movie.)

“(Themes from) The Man with the Golden Arm” reached No. 14 on the Billboard chart in 1956, written by Bernstein and performed by Richard Maltby and His Orchestra.

The film diverges from the book in many ways. In the book, Frankie is a morphine addict; in the film, the drug is never named, but it’s obviously heroin: in the one scene where Frankie’s pusher, Louie, administers the drug to him, although the scene was cut down to the bare minimum to appease the PCA, the method is that used as for injecting heroin. The way Louie meets his end in the film is different from that of the book. Finally, the bittersweet way in which the movie ends is very different from the grim ending of the book, in which Frankie commits suicide. Reviewers of the film were kind, though a lot of critics took exception to the ending, calling it contrived, but the film was a financial success despite them. At the end of a long series of court battles, The Man with the Golden Arm was widely released throughout the world, probably because of the publicity it garnered, and earned $4.3 million.

The master was stored in a rented film vault in New Jersey, where intense rainstorms and flooding caused several film elements to be damaged beyond repair. Some of these film elements included the original camera negative and optical track negative. Although the original elements were destroyed, two fine-grain master positives, both with soundtracks, survived and were brought to the Academy Film Archive for inspection and restoration. A new dupe negative and track negative was made at the YCM Laboratory. DJ Audio performed the audio transfers and Audio Mechanics completed the digital audio restoration. It was restored by the Academy Film Archive with funding from The Film Foundation and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. The film is in the public domain.