- Industry

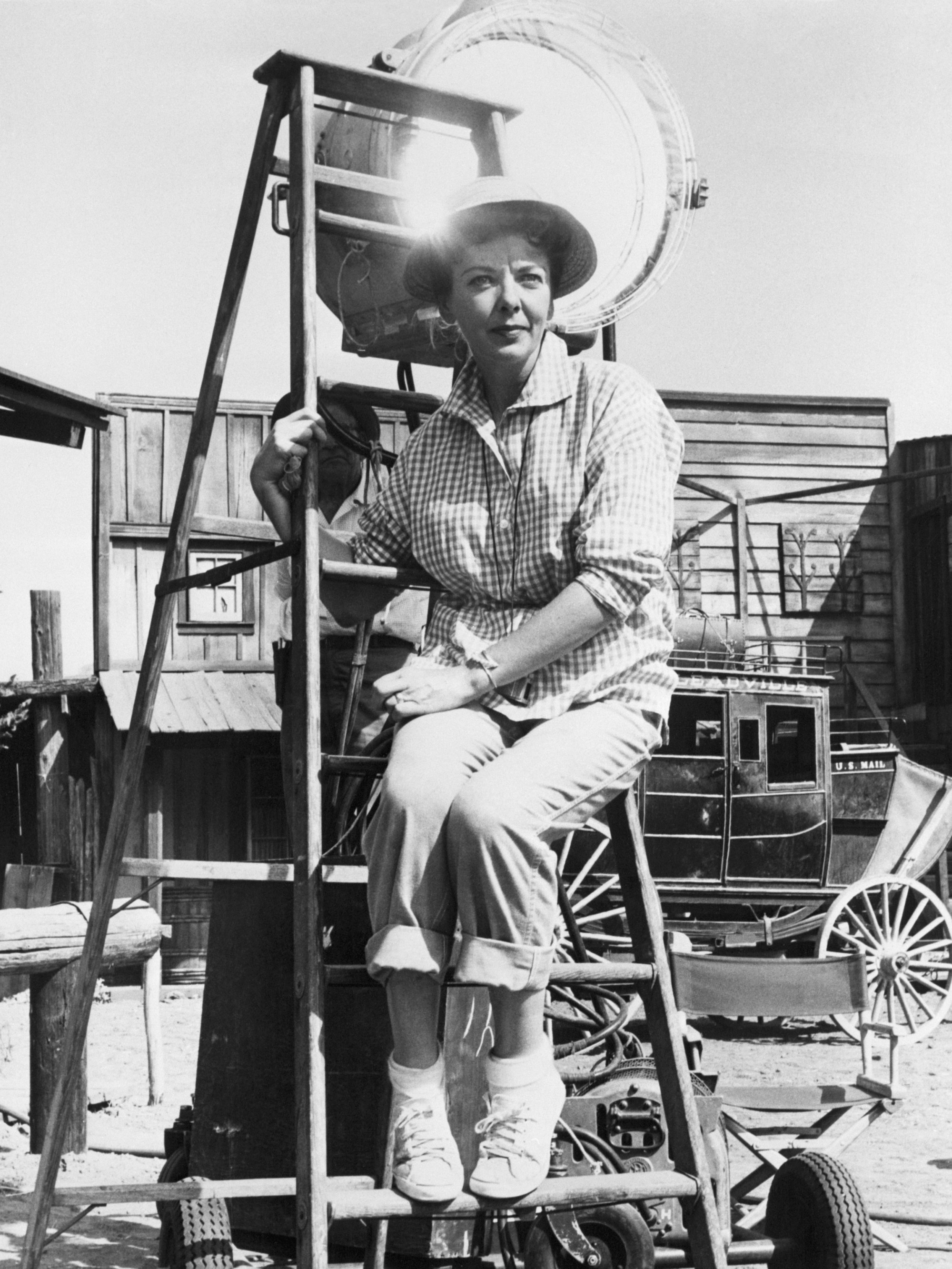

Ida Lupino, One of the Pioneering Woman Directors

Sired into an acting dynasty dating back 300 years, Ida Lupino was born in post-war 1918 London, daughter to an actress mother and a music hall comedian father. By age ten, she had memorized all the leading female roles in Shakespeare’s plays. She attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art at the age of 13, passing herself off as being the student minimum age of 15. She would have preferred to be a writer, but the Lupino family history destined her to take the stage as an actor.

She played leading roles in five British films in 1933, usually as the vampy bad girl. This caught the attention of Paramount, which brought her to Hollywood, signing her to a six-month contract, later extending it to five years. While making good money, she was cast in insignificant roles in bad movies. She refused to be a servant girl in Cleopatra. Only 17 and two years into her contract, she was put on suspension — a status she became very familiar with under the studio system. She fought for a serious role in Peter Ibbetson and was rewarded for her good performance with a new contract, but after that, the roles still didn’t improve. Hedda Hopper advised Lupino that she would probably be taken more seriously as a dramatic actress if she shed her sexy vixen image, and she took the advice. She married actor Louis Hayward in 1938 and starred in a dozen B-movies before William Wellman chose her for a breakthrough role in an adaptation of a Rudyard Kipling story, The Light That Failed (1939).

Warner Bros. offered her a contract, and her femme fatale role in Raoul Walsh’s They Drive by Night (1940), opposite George Raft and Humphrey Bogart, stole the movie and led to the hit High Sierra (1941), where she had top billing over Bogart. Lupino laughingly referred to herself as “the poor man’s Bette Davis,” taking roles that Davis refused. Her husband enlisted in the Marines after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. Alone and out of work, she took a role in The Hard Way (1943), winning the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress. Hayward came home from World War II with what would probably now be called PTSD, and they divorced.

Lupino left Warner Bros. in 1947. She spent a great deal of time at odds with Jack Warner, suspended for refusing poorly-written roles that she felt were beneath her dignity. For 20th Century Fox, she appeared as a nightclub singer (using her own voice) in the film noir Road House (1947), and On Dangerous Ground (1951), where she stepped in to direct for several days when Nicholas Ray was ill.

Lupino used her time on suspension well, observing directors, cameramen and editors, learning the craft of moviemaking. She was often bored and uncomfortable with acting and thought other people on the set did all the interesting work.

She became an American citizen in 1948. That same year, her marriage to executive/producer Collier Young led to the couple forming an independent company, Emerald Films, later renamed The Filmakers Inc., with the goal to make socially conscious, low-budget films and bring realism to the screen.

Dominated by men and bound by the restrictive Hays Code, postwar Hollywood offered little support for a female director who sought to make unique films on controversial subjects. But Lupino bucked the system, writing and directing a string of movies that explored the dark underside of American society.

The Filmakers’ first film in 1949 was Not Wanted, about an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. This was also the first time she took the director’s chair — on the third day of filming, director Elmer Clifton had a heart attack and Lupino stepped in as director to finish the film. She didn’t take credit out of respect for Clifton. It turned out to be a big success.

Her first director’s credit was Never Fear (1949), a film about polio, which she had personally experienced at age 16. She shot much of the film at a rehabilitation center with recovering victims among the cast. Lupino joined the Directors Guild in 1949 when a female director was unheard of. She was the only working woman in the union (and only the second woman ever to be admitted, after Dorothy Arzner, who was active from 1938 to 1943). It can’t have been easy to earn the respect of all-male crews, but Lupino planned her shots carefully and worked fast. The words on the back of her director’s chair speak volumes — “Mother of Us All.”

Howard Hughes was looking to distribute low-budget feature films with his RKO Pictures. He agreed to finance and distribute three Filmakers’ pictures while leaving them total control over the content and production. Outrage (1950) was about rape, which at the time was such a taboo subject that they couldn’t even use the word (it was addressed as criminal assault).

In 1951, Lupino divorced Young to marry actor Howard Duff, widely known as a playboy bachelor. Their daughter Bridget was born six months later.

By the 1950s, the mood of the country had become conservative and paranoid with McCarthyism, and the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed people with suspected communist ties. The big Hollywood studios created a blacklist that ended many careers. They played it safer than ever, but Lupino persisted in showcasing socially relevant issues.

The Hitch-hiker (1953) made her the first woman to direct a film noir thriller, her most purely cinematic venture. The opening title card was “The true story of a man and a gun and a car.” It was shot on a shoestring budget and was a financial success. The Bigamist (1953), in which Ida was the first woman to direct herself as an actor, did not do well at the box office and was her final picture for the company.

Completely out of funds and unable to compete with the big studios, the Filmakers production company ceased operations in 1955. Duff had been blacklisted and could not find work. Their marriage was already stormy due to Howard’s drinking and infidelity, which led him to disappear for weeks at a time. Lupino needed to work so she turned immediately to television, acting in and directing episodes of top U.S. TV series.

In the 1960s she was the first female director, as well as the most prolific director of America’s hottest TV shows such as Bewitched, Gilligan’s Island, The Fugitive, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, 77 Sunset Strip. The 60-plus TV episodes she directed make up the vast majority of her body of work behind the camera. Her ability to work quickly and within budget proved to be a bankable asset. She was the only person to both act in and direct episodes of The Twilight Zone, as well as the only woman to have directed an episode. She also directed a feature, The Trouble with Angels (1965), starring Hayley Mills as a young girl at a Catholic boarding school and Rosalind Russell as the mother superior, which turned out to be her last theatrical film as a director.

Lupino continued working as an actor until the end of the 70s, mainly in television.

She did 19 episodes of Four Star Playhouse, an endeavor involving partners Charles Boyer, Dick Powell and David Niven. She and Duff starred in a sitcom she created for the two of them, Mr. Adams and Eve from 1957 to 1958, in which they played married film stars. She guest-starred in many of America’s top TV shows from 1954 to 1979, including Bonanza, Batman, The Mod Squad, The Streets of San Francisco, Columbo, Police Woman, Charlie’s Angels. That year she acted in Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner with Steve McQueen, and her final acting appearance was in the 1979 film My Boys Are Good Boys.

Lupino died at age 77 from a stroke while undergoing treatment for colon cancer on August 3, 1995. In her 48-year career, she acted in 59 films, and she is widely regarded as the most prominent woman filmmaker during the Hollywood studio system in the 1950s. The National Film Registry selected two of the films she directed, Outrage (1950) and The Hitch-Hiker (1953) as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” She created a distinctive directorial style that was both highly expressionistic and grittily realistic.

Lupino has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contributions to both film and television. We remember her achievements as an actor and as a pioneering director that opened doors for the women directors of today.