- Golden Globe Awards

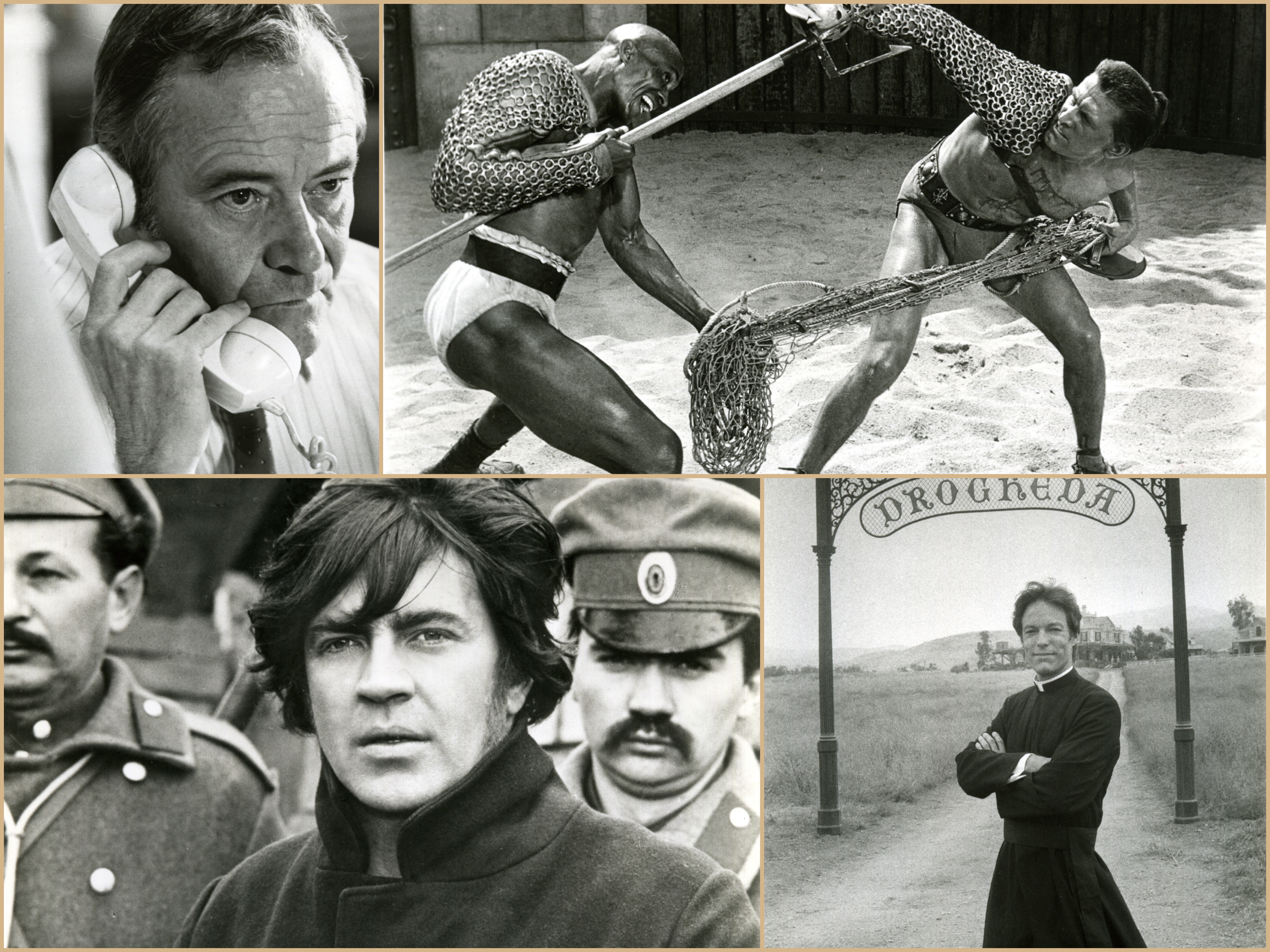

Remembering Producer Edward Lewis, Golden Globe Winner

Edward Lewis was born on December 16, 1919, in Camden, N.J., and at first, planned to become a dentist, and went to college, where, ever feisty, he was on the wrestling and boxing teams. World War II intervened and he left dental school before graduating, to enlist and serve at a military hospital in England. Discharged, he moved to Los Angeles, where he met and married Mildred Gerchik, a Brooklyn transplant with a radical and social activist family background: her mother was a garment industry organizer, and a brother had fought in the anti-fascist Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War.Mildred, who died earlier this year, helped develop Lewis’s “deep and powerful commitment to social justice”, said their daughter, Susan who recalled how the young couple became movie producers. “They went to a social gathering where someone presented a screenplay in progress. My parents went home and said to each other, ‘We can do better than that.’ ”For their first project, they adapted a play by Honoré de Balzac into a historical comedy, The Lovable Cheat (1949). Variety panned it, saying that it “misses on practically all counts.” Undaunted, Lewis produced for CBS two of the first drama anthology series on TV, and soon joined Kirk Douglas’s Bryna production company as a writer and producer. Their collaboration on Spartacus (1960) would change Hollywood’s history- one of the darkest and most shameful chapters, the blacklisting. A streak of anti-communism running through American life was inflamed after the end of World War II when Senator Joseph McCarthy in the Senate and the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) led relentless investigations and hearings of alleged communists. Hollywood was a prime and visible target, and the most famous victims were the Hollywood Ten – nine screenwriters and a director who refused to cooperate and charged with contempt of Congress, were jailed by the HUAC and placed by the studios on a ‘do not employ’ blacklist.Mildred Lewis had recommended “Spartacus”, the novel by Howard Fast (another blacklist victim), to her husband, and he brought it to Douglas’s attention.Not satisfied with author Fast’s screenplay of his book, Lewis and Douglas turned to blacklisted prolific writer Dalton Trumbo, who had been working underground since 1950, having written some 18 movie scripts, all under assumed names. The studios paid little and were afraid to give him credit. Trumbo recalled earning an average fee of $1,750 per film and said, “None was very good” (Two of them, however, won the Oscar: The Brave One in 1956 and Roman Holiday in 1953).Lewis used a subterfuge. As Trumbo produced script pages, Lewis would present them to the studio under his own name. Douglas would later write in his memoir “I Am ‘Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist” (2012): “Every time Eddie Lewis told someone he was writing Spartacus, it embarrassed him…The revelation of Dalton Trumbo’s involvement with Spartacus could shut down the entire picture. So Eddie continued to play the producer-turned-writer, a charade he hated.”But the zeitgeist was ready. In 1957 CBS television allowed the hiring of blacklisted talent. By 1959 former President Harry S Truman called the HUAC the “most un-American thing in the country today”, and in January of 1960 director Otto Preminger announced that he engaged Trumbo to write the script for his forthcoming film production of Leon Uris’s bestseller “Exodus”. Lewis and Douglas demanded that the studio pay Trumbo and credit him. Having invested heavily in Spartacus, some $70 million in today’s dollars, the studio had little choice. Exodus was released on October 1960 by Universal International which became the first major movie studio to give screen credit to a blacklisted writer. “When Trumbo set foot on the studio lot of Spartacus,”. Douglas wrote, “the blacklist was broken.” Although its effects remained for decades, and the harm it caused was never fully repaired.