- Film

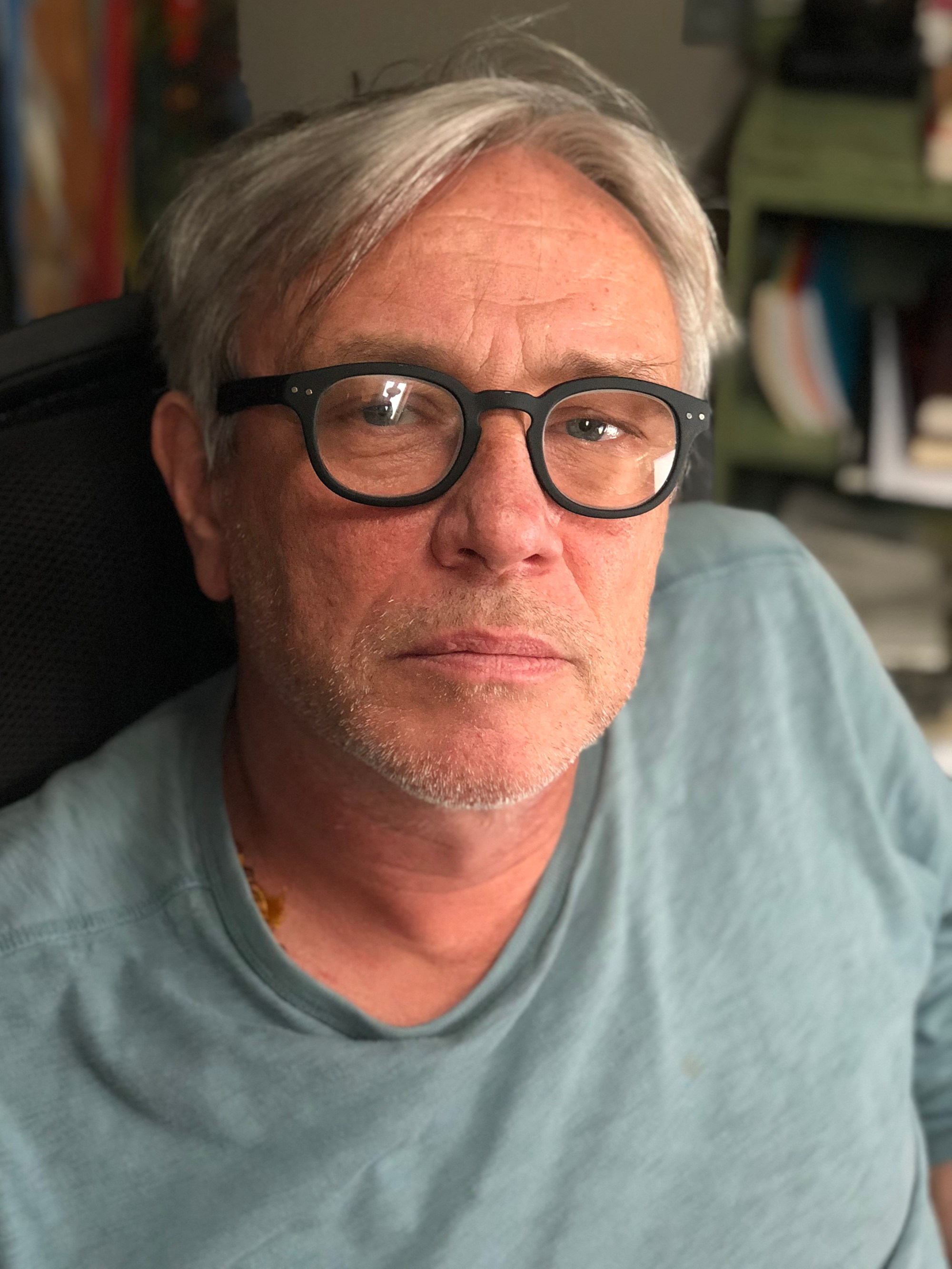

“The Ghost of Richard Harris” – The Man Behind the “Hellraiser” Image

Director-screenwriter Damian Harris, the eldest son of legendary British actor Richard Harris, has collaborated with his two brothers, actors Jared (Chernobyl, The Crown), and Jamie (Carnival Row, West Side Story) on the long-awaited documentary about their father, The Ghost of Richard Harris.

Regarded, alongside Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton, as one of the greatest actors of his generation, Harris was born in Limerick, Ireland, and performed in numerous stage productions. As well, Harris performed in over 60 films and thirteen TV productions. Nominated twice for an Academy Award for This Sporting Life and The Field, Harris won the Best Actor at Cannes for This Sporting Life (1963), a Golden Globe for Camelot (1968), and was nominated for The Field (1991). Some of his other film roles include those in Unforgiven (1992) and Gladiator (2000), and the first two Harry Potter films (2001 and 2002).

Harris had a number one singing hit in Australia, Jamaica, and Canada, and a top 10 hit in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States with his 1968 recording of Jimmy Webb’s song, MacArthur Park.

Through the heartfelt recollections of his three sons, The Ghost of Richard Harris reveals his public and personal personas to have been quite separate from each other. The documentary, directed by Adrian Sibley, offers an informative, and, at times, rather sensitive peek into the man behind the “hellraiser” image. It also commemorates the 20th anniversary of his death.

We catch up with Damian Harris on the phone to talk about his father’s trajectory from Ireland to Hollywood.

Congratulations on this fantastic documentary. How did it come about?

Before my father passed away, he’d begun writing his autobiography, and it was in its nascent stages when he died. We’d been approached about authorizing both biographies and documentaries on him and we decided to go with Adrian Sibley, who had made documentaries on Anthony Hopkins (A Taste for Hannibal) and Bruce Robinson (The Peculiar Memories of Bruce Robinson). Adrian and my father had met to discuss the idea of a documentary and had gotten on really well.

So the three of you continued with Adrian where your father left off.

Adrian didn’t want to do a straight documentary. It was his idea of my father starting as Dickie in Limerick and then coming to England; and with success came the creation of Richard Harris.

It was interesting to see the documentary from his sons’ point of view.

Yes, three of us, 20 years after he passed, delved back into who our father was and also to see if there were things that we’d learned that we didn’t know.

Well, that was my next question. What did you learn that you didn’t know about him?

I was really struck by what a strong, individual man he was, his way of thinking and how he approached life, which I think was more interesting than just recounting – he did this movie, he did that movie, or did this album.

And evidently, he had two very disparate personas – Dickie and Richard.

I never knew Dickie because he was already creating Richard Harris by the time I was a young kid. And so, that aspect of the film was completely new to me. And he kept the two separate from us. As kids growing up, we’d go to Kilkee for the summer, and we’d meet our Irish cousins and family. In the 1990s, he organized a family get together for the Harrises from all over the world, at Dromoland Castle, outside of Limerick. And that was the first time he showed us the home that he grew up in, where he was as a boy. It’s a part of my father that I had no idea of, and he didn’t really share with us. It was there in his poetry book, “I, in the Membership of My Days,” with the poems that relate to who he was growing up.

As kids were you aware of his iconic status? Or did you not know that until you got older?

We knew of him being a film star, we definitely knew that. Yeah, because that was Richard Harris and that’s who we knew him as and who he presented to us. It was a role he played, in a way.

The fact that the three of you went into the same business – was it a burden in any way of being “the son of?”

Not really. Definitely not here in Los Angeles. I was going to be a director and a writer. So, it was slightly different. So, if people found out, there would be a curiosity, but there were no expectations on me in terms of measuring me against who he was or the career he had. I think for my brothers, it’s probably different. In fact, Jared talks about it in the film.

What’s your last memory of being with him?

We always talked about working together and we’d optioned a book before called “The Cost of Living Like This” by James Kennaway. We couldn’t agree on the script, so it got shelved. Then, in the last year of his life, we decided to try it again with a different book, called “Pop” by Kitty Aldridge. Kitty and I wrote the script and my father was really excited, because it was something that he responded to. It was about a grandfather and a granddaughter, and he had a very close relationship with my daughter, Ella. So, it was a positive time for the two of us, and of course ultimately sad, as we didn’t get to do it.

Watching the documentary, it seems he’s still very much a part of your lives?

Yes. He’s been in our lives since he passed. He’s very present for the three of us, and with the rest of our family, including my daughter and my daughter’s family as well, who my father was very close with. He’s very much a figure that’s still living here.

Was he supportive of his three sons going into the business? Many actors would prefer their offspring to go in a different direction.

He was of the mind that you do what you want and he would be supportive of that. I know that with both Jared and Jamie, he was supportive and would go to see them in either a school production or a play and then would just go, “Yeah. Absolutely, you’ve got to go for it!” It was the same with me. I went to film school, and when he saw the shorts I made, he was very encouraging. And then the same thing when I finally made feature films. He was a big cheerleader.

He was often described as a hellraiser. Does that resonate with you?

It’s just the person I knew. It was a moniker that he had a hand in creating for himself because it was part of who Richard Harris was, the character he created. So, he was public about it. Did not bother him. It added to his fame, and yes, I was aware of it, absolutely, growing up. I was also aware of the other aspects to him, which he didn’t share with the public and the press. He could be shy, and he was extremely sensitive. It was a contrast. The “hellraising” came at a time when it was glorified. He wasn’t the only one, and [that behavior] was also seen as adding to their masculinity, allure, and fame. And so, when he would get into whatever type of hell raiser behavior, it would be in the papers the next day.

What do you think he’d make of this ultra-PC world that we’re all living in now?

Oh, he’d absolutely hate it. I guess, he would’ve got condemned quite heavily.

Did he have any kind of aversion to Hollywood?

Well, he claimed he did. But then he actually welcomed it and dove into it. And he was at the end of the glittering Hollywood era, that he wanted to feel part of. Camelot was a perfect example of a big, old school, Hollywood musical, but they were also making films like Easy Rider. And so, that transition was happening. He went there to experience that. I think he recognized that being part of that Hollywood system, you could lose what makes you unique. And so, there was a dismissal of it, or a suspicion of that, as well of Hollywood.

How difficult was it to get Russell Crowe and Vanessa Redgrave to appear in the documentary?

I don’t think it was. Russell and my father were close. Even way after Gladiator, they remained close. When Russell was filming Master and Commander he flew from the set to be at my father’s funeral. I think the same with Vanessa. The logistics of it might have been hard but getting them was not.

What would you like audiences to take away from watching this?

That he was an interesting man, an original man. And I think that his way of thinking and approaching life is as relevant today as it was when he was living it, whether it’s the sixties or seventies, eighties, or nineties. And that’s aside from the long, long career he had, and all the things that he did. It ties into the question earlier about how would he react to the current social mores? I think he stands out in contrast to that. And that’s interesting. It’s always interesting to have a contrasting point of view, even if the person’s not here and hasn’t been for 20 years.

What do you think he’d say if he could watch this?

Well, two things. One, he would always be critical because he couldn’t help himself. That’s his personality. And secondly, I think he’d be very moved to have all these people come and talk about him. You see in the documentary how he impacted other people’s lives. And I think that would’ve moved him.

And can you tell me a bit about what you are doing now?

I’ve just finished postproduction on a movie called Brave the Dark that I directed and did some writing on. It’s with my brothers Jared and Jamie, and a young Australian actor Nicholas Hamilton.

What is Brave the Dark about?

It’s a true story, set in 1986, in a rural area of Pennsylvania, Lancaster, about a local hero, Stan Deen, a high school teacher, and his relationship with a student, Nate, who’s 17. Nate’s life is screwing up, and he is shunned and abandoned by the community. And so, Jared’s character, Stan, steps in to try to help him, not realizing exactly how hard it’s going to be. It’s about two people both stuck in a situation they need to move on from, who become the catalyst for change in each other’s lives. Ordinary lives whose story is not ordinary at all but is in fact extra-ordinary. It is about the simple goodness in people.