- Film

Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Satyajit Ray-My Years with Apu; A Memoir

“Even a year before the autumn afternoon in October 1952 when I started shooting Pather Panthali in a field of white kaash* flowers, the thought of taking up filmmaking as a career hadn’t occurred to me at all.” So writes legendary director Satyajit Ray, in the opening paragraph of “My Years with Apu: A Memoir.” It took him three years to complete that groundbreaking masterpiece released to universal acclaim in 1955. A new cinematic voice could be heard that helped put Indian cinema on the world map.

In his memoir, he mostly describes the long-gestating artistic genesis and the arduous making of the film and its two sequels Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sensar (1959), which formed the Apu trilogy. Sorting through the puzzle of memories, he also tells about his growing up in the West Bengal city of Calcutta where he was born in 1921. Vivid recollections compose a colorful kaleidoscope that gives the reader a better idea of what shaped his life.

“I became a film fan while still at school”, he recalls. “I avidly read Picturegoer and Photoplay and neglected my studies and gorged myself on Hollywood gossip purveyed by Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. Deanna Durbin, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were favorites whose films I saw several times just to learn the Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern tunes by heart. In my early college years, my interest shifted from the stars to directors. My intense fascination for Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Gary Cooper, Cary Grant was giving way to an interest in Ernst Lubitsch, John Ford, Frank Capra, William Wyler, George Stevens. When I watched a film, I was no longer absorbed in just what the stars were doing, but was also observing how the camera was being deployed, when the cuts came, how the narrative unfolded, what were the characteristics that distinguished the work of one director from another.”

Still, he confesses, “I had grown up with the notion that nothing was more desirable for a young man than financial security. And I had in mind to become a commercial artist. Both my grandfather and father were painters and illustrators and I had a natural flair for drawing.” He joined a British advertising firm, but “although it provided me with my daily bread and butter, what really mattered was music and film.”

He first became aware of Pather Panchali in 1944 when he was offered to design the illustrations for an abridged version of the 1929 Bibhuitbhusan Bandyopadhyay’s beloved classic. “It was plainly a masterpiece and a sort of encyclopedia of life in rural Bengal. It dealt with a Brahmin family, an indigent priest, his wife, his two children Apu and Durga, and their elderly cousin, struggling to make ends meet.” A friend suggested it would make a very good film. “An idea I tucked away in the back of my mind.”

Flash forward to 1947. India became independent and Ray created a cinema club which he named the Calcutta Film Society. The very first screening was of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. And “around that time I wrote my first article on cinema called What is wrong with Indian Films?, published in the leading local English daily.” He quotes part of it. “What it needs today is no more gloss, but more imagination, more integrity, and a more intelligent appreciation of the limitations of the medium and, above everything else a style, an idiom, a sort of iconography which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.”

In February 1949, Ray met Jean Renoir who was in Calcutta to prepare for The River. He accompanied him scouting locations in the countryside. When the French director asked him if he was interested in becoming a filmmaker and if he had an idea in mind, Ray gave him a brief outline of Pather Panchali. “He encouraged me and advised me to not borrow from American films and turn aside from the Hollywood world.”

In his spare time, he started to write scripts, “just for the fun of it, as I still did not realize it was the prelude to my giving up my job and taking up film as a profession.” Another determining event was a six-month trip to Europe with his wife in 1950 during which he saw 99 films! “The real impact came from The Bicycle Thief, which I found moving beyond words” he remembers. More importantly, it reinforced his conviction that neo-realism was the right approach for him too. It was a major breakthrough. “Who said you could not use non-actors?”, he wondered. “ Who said you could not shoot in the rain, that you had to use make-up, that slickness was a criterion?”

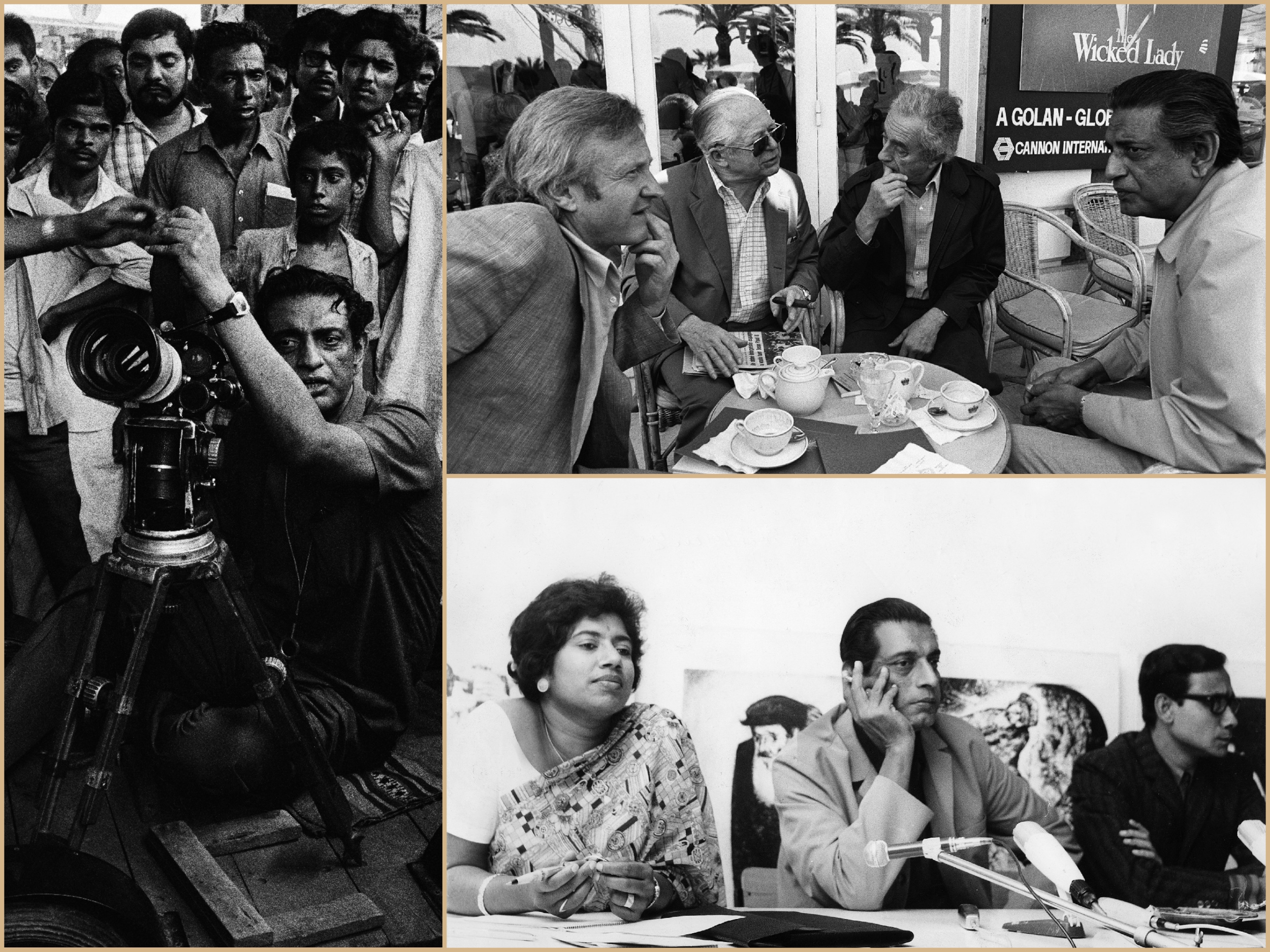

(Left) Filming The Golden Fortress (Sonar Kella), in Calcutta, 1973; (top, right) with John Boorman, Billy Wilder, and Michelangelo Antonioni at the Cannes Film Festival, 1982; (bottom, right) with an interpreter, at a press conference at the Berlin Film Festival, 1969.

ullstein bild/nik wheeler/ralph gatti/getty images

During the return passage to India, he completed the treatment of Pather Panchali. He was now ready to embark on a journey that would change his life. But, first, he had to secure the rights to the book. The author had just died but his widow agreed to sell it to Ray once he could find financing. Not so easy for the aspiring director as several potential backers declined to invest in his project. “There was never a developed screenplay,” he explains, “but only a sheaf of notes and sketches that described the film in sequence like a storyboard.”

From the start, his vision was very clear. “I knew that Pather Panchali would have a vastly different look from the usual Bengali films. I wanted my film to look as it was shot with available light à la Cartier-Bresson, paying homage to the photographer I considered the greatest of them all.” The search for the perfect Apu dragged on until Ray’s wife Bijoya by accident spotted a kid on the playground adjacent to their flat. Subir Bannerjee was eight years old and had never acted before. “I had to devise all kinds of tricks to get the right kind of performance and expression out of him. Fortunately, Subir looked exactly right for the part, otherwise, it would have been a disaster.”

Ray depicts in great detail the hardships, the innumerable hurdles encountered making the film, the slow progress as the money kept running out. He had to keep his daily job and could only film on Sundays as long as meager funds were available. At some point, he remembers that “my wife had to pawn her jewelry and I had to sell some of my records and rare books to pay for some of the shooting.”

All along, he never lost faith. By late 1953, only one-third of the film was in the can. Shooting had stopped and “I was back at my desk designing ads and books. I don’t honestly think I ever had hope of resuming work on the film.” After an eight-month interruption, he could, in the early part of 1954. And financial assistance from the West Bengal government had materialized.

The last step was to add music. Ray chose his friend Ravi Shankar who composed a haunting and memorable sitar-based score in a single eleven-hour marathon recording session.

Pather Panthali was finally completed and the result surpassed Ray’s expectations. “It actually resembled no other film made in India or elsewhere in the world,” he recalls. “Above all, in spite of the influences on me of Hollywood, Renoir and De Sica, the film looked Indian to the core.” Mission accomplished. On May 3rd, 1955, the film had its world premiere at the MOMA in New York, before its release in Calcutta later in August. The positive reactions were a relief for Ray. Even though, as he states, “some ministers and officials at the Central Government had taken objection to a film portraying such unadulterated poverty.” They were concerned it would project not the best image of the country abroad. But “Prime Minister Nehru himself saw it and was moved and quick to silence all opposition to the film’s participation at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival.” It ended up winning a Special Jury Prize as Best Human Document.

“The success of Pather Panthali helped in a decision that had been forming in my mind for some time, to give up advertising and take up filmmaking as a whole-time profession,” Ray reminisces. “But before giving up such a lucrative job, I had to find a story and a backer for my next film.” After discarding many Bengali novels, he realized he was not yet ready to let go of Apu, who would return in Aparajito, now a teenager. Released in October 1956, it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival a year later. With Apur Sansar in 1959, the Apu triptych was concluded…

Admirers of Satyajit Ray will relish reading the book as it provides a unique insight and richly detailed anecdotes of one of the greatest filmmaker’s process and personal journey at the beginning of his career. With his doubts and angst, the frustrations and joys, the exhilarating rush when all the elements of the artistic vision gel and fall into place, the challenges of working with nonprofessional actors, the unpredictability of it all.

“My Year with Apu: A Memoir”, was published posthumously in 1994, two years after Ray’s passing at the Belle Vue Clinic in Calcutta, at age 70, not far from his apartment on 1/1 Bishop Lefroy Road, where he had lived for many years.

*A tall herbaceous plant with elegant fluffy feather-duster like tips, indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. It grows perennially in the fall.