- Industry

Clint at 90

“You never know if you are going to get there.” This was Clint Eastwood’s spontaneous reaction to the HFPA last December when reminded that his 90th birthday would be coming up six months later on May 31st. “60- something years ago when I started acting, you never think it is going to end and you hope it is going somewhere. You are lucky that it does and then you look back and go: why I am still here and why I am not in an old folks home. You kind of just keep doing the best you can. So I am just there and it’s been a good ride and I will just ride along on my make-believe horse!”

Indeed, the journey has been quite rewarding, not least for his legion of fans who relish seeing him more active than many of his octogenarian peers, who have made themselves scarcer in front and behind the camera. Until recently very prolific, Woody Allen, 83, is now ostracized. Warren Beatty, at 83, has been silent since his last opus, Rules Don’t Apply, sank at the box-office. Robert Redford, 84, announced that he was retiring two years ago. Bob Rafelson, 87, has not made a film since 2002.

So Eastwood finds himself, de facto, one of the last real Hollywood giants standing. And of course an undisputed true legend. Even if he has often said that he does not see himself as such, only admitting, when pressed: “It’s fine. It’s very nice. I’d rather be called that than something less flattering.” One would think he has nothing more to prove after winning four Academy Awards and five Golden Globes, including the Cecil B. deMille statuette. Not Eastwood whose unique productivity and extraordinary longevity, both personal and professional, are astonishing by Hollywood standards. Maybe a clue lies in the song heard at the end credits of The Mule, the last time we saw him on screen.…Its title? Don’t Let the Old Man in.

Case in point. It was 1952 and Clint Eastwood had moved to Hollywood, hoping to make it as an actor after completing his military service. At a friend’s suggestion, he started to take acting classes. Two years later, after many unsuccessful auditions, he finally got a contract at Universal for 75 dollars a week but was quickly dropped. “You have to take a lot of disappointments as an actor,” he acknowledged when reminiscing about that period. “That is the nature of the beast. I knew it was a very high-risk profession. You’re either in the basement or at the top. I remember going five to six months without any job. It was frustrating. I was at the very bottom. I thought about quitting until one day someone suggested I go to CBS to see about a TV series.” He got the part of Rowdy Yates in Rawhide in 1958. “It was the first steady job I had and I made up my mind I was going to learn as much as I could about the whole process and stick with it, regardless of even sometimes getting tired of doing the same character week after week.” No wonder, he told the HFPA, that after a while, “his dream was to get off of Rawhide!”

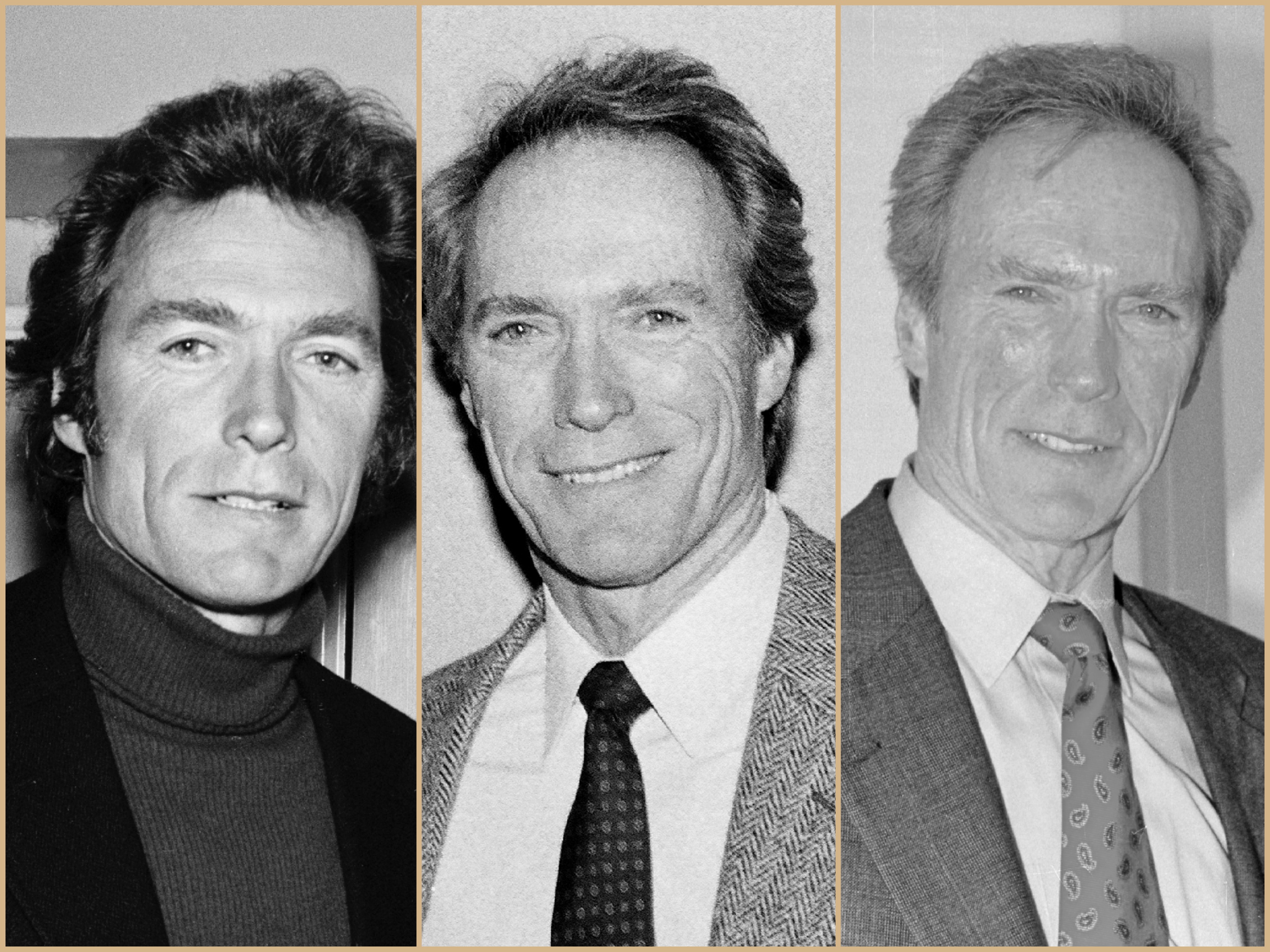

Clint and the HFPA: portraits from press conferences in 1973, 1988 and 1992.

hfpa archives

And he did with a choice that would change his career forever and helped him become a star. It’s a story he had told many times. One day in April 1964, he landed in Rome. “A suitcase in one hand and the script of Per Un Pugno di Dollari in the other. I met Sergio Leone. He spoke no English and I spoke no Italian. He knew good morning and I knew Buongiorno! It was a great experience. I enjoyed making all the three pictures in Spain, near Almeria. After The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Sergio asked me to do Once Upon a Time in the West but I turned him down. I felt I had to move on. I couldn’t get going back doing Italian westerns. It was time to do my own things, try other genres.”

Another smart move. With the release of Dirty Harry in 1971, Eastwood achieved superstardom playing a highly controversial character that he believes looking back was misunderstood at the time. “I think having him being labeled right-wing was not a fair analogy. Neither the director, Don Siegel nor I were right-wing conservatives. But we just found it an exciting detective story featuring a protagonist with an unorthodox mentality, someone who had doubts about the state of the law. Harry Callahan was a guy very frustrated with the political structure of his city, the hurdles he had to leap over, and very concerned with the victims of violent crimes. But it was just a character and sometimes as an actor you are called upon to play lots of parts that philosophically you agree with or you don’t. And when you disagree it is even more of a challenge.”

What about the iconic macho image he went on to be associated afterward with for a long time? “I never wanted to have a particular image. That was sort of created over the years I think because of some of the roles I played. But it did not mean that I wanted to be wielding guns and chase down criminals in the streets of San Francisco or what have you!” In 1968, he had founded his own production company Malpaso, “As a way to control my own destiny’. Very early on, he was determined to avoid being typecast. “I know that at one stage in my career, people did want me to stay in the genre I was popular in. But I went off and did other things and offbeat films. The Outlaw Josey Wales, Honky Tonk Man, Bronco Billy, The Gauntlet, Tightrope. Trying each time a different take on my performances. Sometimes successfully and sometimes not. But you have to try. It is healthy to stretch. If you don’t get up and swing the ball, you’ll never going to hit it, you know. You have to swing it a few times. And sometimes you hit the ball and sometimes you don’t.” When reminded that Richard Jewell, released in December 2019, was his 38th film as director/producer, his reaction was facetiously amused. “When I’ll get to forty, I’ll do a little dance.”

Speaking of rhythm, there’s his longtime fascination with jazz. “When I was a kid music was a constant,” he explained, while discussing his 2003 documentary Piano Blues. “After Fats Waller died, my mother brought home a whole collection of his records. I learned to play the piano by listening to them. He would go on to create many of his own compositions for his films.

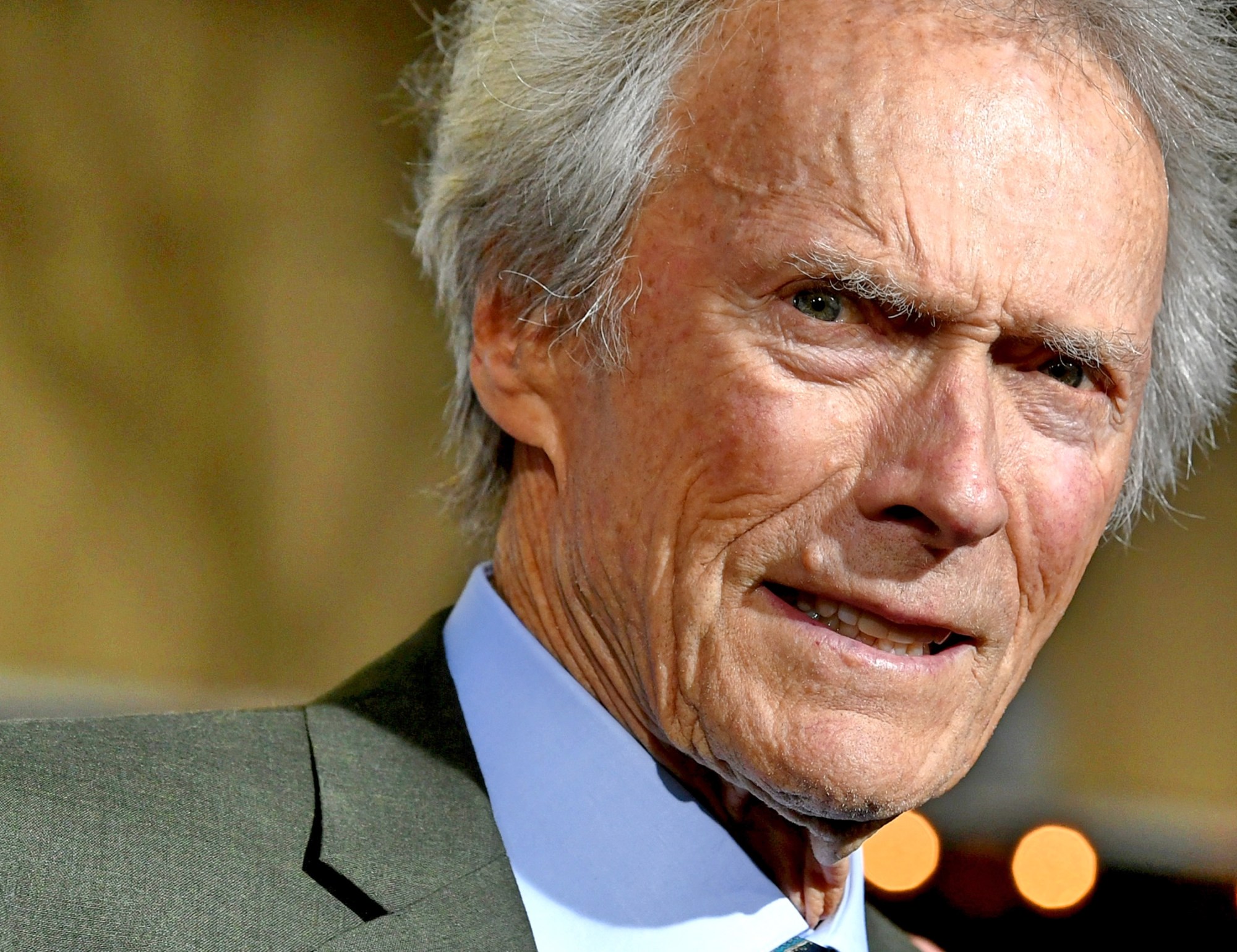

Clint at the Globes: arriving in 2005 (center photo) and winning in 2007 (left) for Letters From Iwo JIma. And at out most recent press conference, for Richard Jewell, in 2019.

hfpa archives

When he directs, he is known for never wasting time, coming under budget and under schedule. Actors marvels that he does only a few takes, never says the sacramental action, and how intimate and relaxed the ambiance on his sets is. He has worked with and directed some of the very best. Bradley Cooper, Kevin Costner, Gene Hackman, Matt Damon, Hilary Swank, Angelina Jolie, Meryl Streep, Morgan Freeman, Burt Reynolds, Jeff Bridges, Tom Hanks, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kathy Bates, William Holden.

So what has kept him going for so long? “When you think you know everything, you realize that sometimes you know nothing. The longer you live, the more jobs you have done, you really still got a lot to learn. And I still work at this stage in my life because I still learn something all the time. I think as long as I do that, I will be happy. If I stop learning, I would shut myself off then obviously I wouldn’t last very long.”

It has been a long journey that still seems to surprise him as he reflects on it. “I can’t explain why that is,” he admitted. “I just hung out a long time and just when you think, well, maybe we should just get rid of him, something pops up and works. So you never know. I thought about it a few times: what gives you a certain longevity, about what I am still doing here, how long do I want to stay. I go back to the adage that it is not an intellectual debate but an emotional one. I’m sure I’ll know someday when I shouldn’t be doing this anymore, or that I am tired, and I’ll figure whatever… But I have never seen that day and never come to that kind of conclusion.”