- Cecil B. DeMille

Ready for My deMille: Profiles in Excellence – Jack Lemmon, 1991

Beginning in 1952 when the Cecil B. deMille Award was presented to its namesake visionary director, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has awarded its most prestigious prize 66 times. From Walt Disney to Bette Davis, Elizabeth Taylor to Steven Spielberg and 62 others, the deMille has gone to luminaries – actors, directors, producers – who have left an indelible mark on Hollywood. Sometimes mistaken with a career achievement award, per HFPA statute, the deMille is more precisely bestowed for “outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment”. In this series, HFPA cognoscente and former president Philip Berk profiles deMille laureates through the years.

Jack Lemmon never had an enemy.

In 1998, when Ving Rhames won his Golden Globe as Best Actor in a TV Movie and called up a visibly embarrassed Jack and gifted his award to hi. He reluctantly accepted.

But why you may ask, since Jack was no stranger to receiving Golden Globe awards, not to mention his Cecil B. deMille.

In fact, he had won four Golden Globes in his remarkable career, but true to his nature, not wanting to delay the broadcast, he left the stage with that award. Rhames was later sent a replacement.

Looking back at his career two surprising things emerge. He remained a contract player with Columbia and Harry Cohn for most of his career; in fact, at one point he signed a three-year extension. Cohn has been vilified by just about everyone who ever worked at Columbia, but not Jack. You never heard a disparaging word from his lips. And because of that loyalty, he was allowed to develop a working relationship with Billy Wilder, at other studios, that has seldom happened.

Jack always wanted to be an actor even though he was an accomplished pianist. And after graduating from Harvard, he studied acting with Uta Hagen finding work as a professional actor on radio and television. By the time he was thirty had appeared in almost a hundred TV shows. It was his Broadway debut in a revival of Room Service that caught the attention of a movie scout, and he was signed by Harry Cohn, who gave him the lead opposite Judy Holliday in It Should Happen to You. Their chemistry clicked, and they followed that with another co-starring role in Phfft.

Because his contract allowed him the leeway to pursue other projects — he seriously had Broadway in mind — when John Ford offered him the role of Ensign Pulver in Mister Roberts, his film career was sealed.

Not only did he win the Oscar for that role, but he also became Columbia’s top star, and they used him to their advantage, giving him forgettable roles opposite Betty Grable (in her declining years), Janet Leigh, June Allyson, even Rita Hayworth.

It was his teaming with director Richard Quine, however, that really got him on the right footing. Starting with Operation Mad Ball, in which he perfected his screen persona, he followed it with Bell Book and Candle, in which his costar, Kim Novak, was Columbia’s designated successor to Rita Hayworth (but it was James Stewart who got the girl.)

Billy Wilder must have seen something in him and cast him in Some Like it Hot, which required him to play a role in drag, for which he won his first Golden Globe as best actor in a comedy. The film was a smash hit, and it established Lemmon as a major star.

No more supporting roles for him.

Back at Columbia, he was reunited with Director Quine on Doris Day’s It Started with Jane, commencing a collaboration that stretched over ten years, which actually began when Quine directed his screen-test for Mister Roberts. But even more important was his seven-picture collaboration with Billy Wilder, who was quoted as saying “Happiness is working with Jack Lemmon,” and the feeling was mutual. A third partnership was with Blake Edwards, who was to direct him in his best actor Oscar-winning performance.

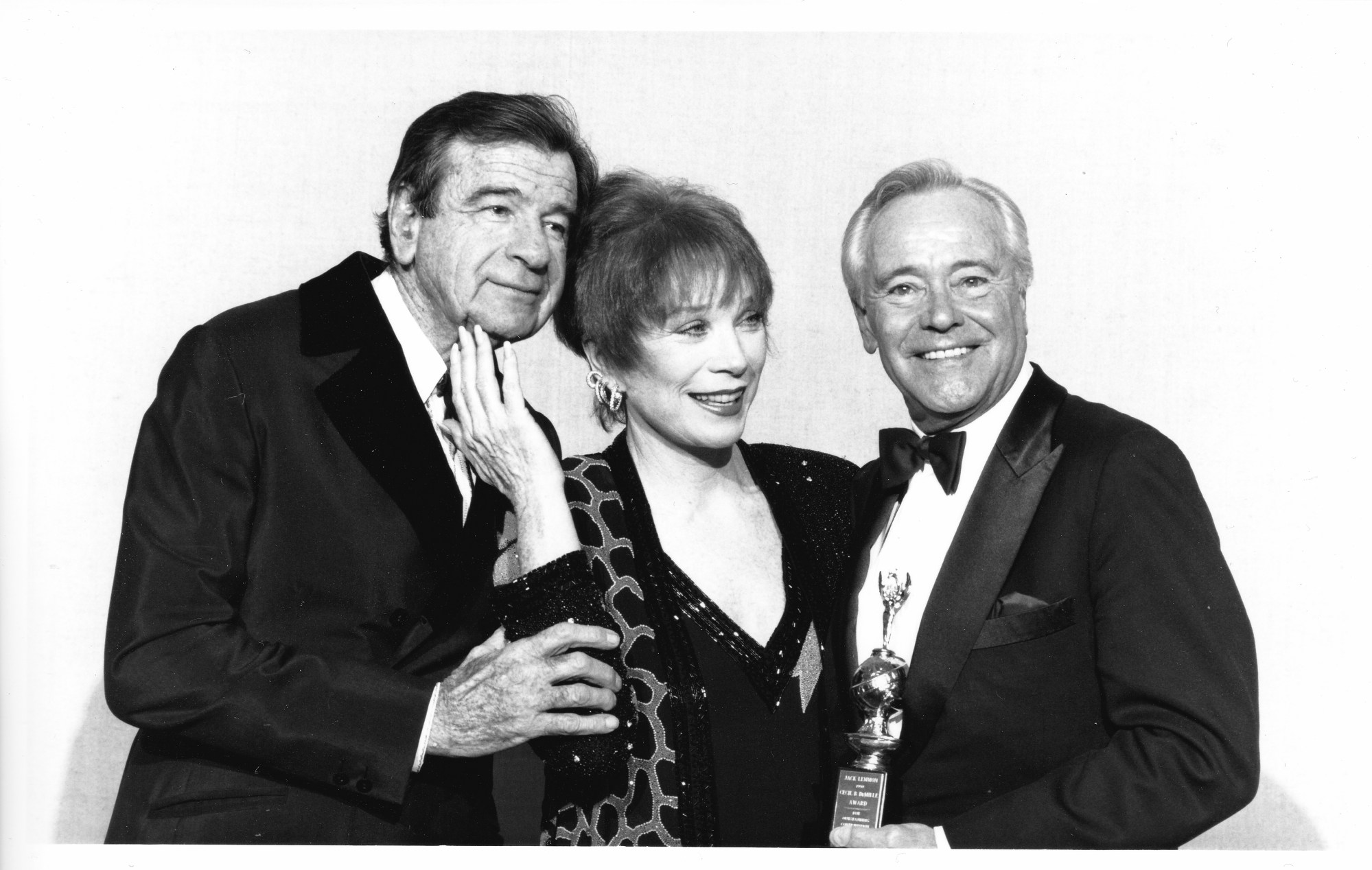

Essentially the best of Lemmon can be seen in the films he made with these three directors. But it was his next movie Wilder’s The Apartment, which made him an icon. Playing opposite Shirley MacLaine, he won his second Golden Globe in two years as Best Actor in a Motion Picture-Comedy. The film became an instant hit and remains perhaps his most popular title. It won both the Golden Globe and Oscar as best picture and international recognition; in fact, in the 2002 Sight and Sound poll of critics and directors, it was voted the 14th greatest film of all time.

His follow up films were less auspicious.

There were two Quine directed movies The Wackiest Ship in the Navy and The Notorious Landlady, this one with Quine’s then paramour Kim Novak, but neither measured up. Then, exercising his option to make outside films, this one for Warner Bros., and again working with Blake Edwards, he chose to do a drama Days of Wine and Roses, for which he was rewarded with a Golden Globe nomination.

He followed that with his biggest box office hit, Irma La Douce, a West End and Broadway musical success, which director Wilder stripped of its musical trappings and turned into a farce, and which the public loved. Once again Jack was nominated for a Globe, and again the next year for Under the Yum Yum Tree, working this time with director David Swift, a collaboration that proved so successful they followed it with another comedy, Good Neighbor Sam. Collaborating again with Quine he made the delightful How to Murder Your Wife, which introduced to American audiences the inimitable English comic Terry Thomas. Blake Edwards was the impetus for the hugely expensive The Great Race which reunited him with his Some Like it Hot costar Tony Curtis but which ended up decidedly less than the sum of its promising parts.

To the rescue came Billy Wilder’s black comedy The Fortune Cookie, which made Walter Matthau a star and which was the beginning of a long professional and personal friendship for the two of them. Their follow-up film, The Odd Couple, began his long association with America’s all-time most successful playwright, Neil Simon, and it’s hands down their biggest commercial success. Again Jack was nominated for a Golden Globe as Best Actor in a Motion Picture-Comedy.

He tried directing a movie, the respectable Kotch, for which Matthau was nominated for both an Oscar and a Golden Globe, before making The April Fools with Catherine Deneuve and The Out of Towners with Sandy Dennis. The War Between Men and Women was a misfire, but the delightful Avanti! which didn’t get much love except from the Hollywood Foreign Press gave Jack his third Golden Globe as best actor in a comedy. Again Billy Wilder was his director.

The uncompromisingly dramatic Save the Tiger earned him his Oscar as Best Actor in a Leading Role, some 18 years after his Mister Roberts win. After that, he did Wilder’s critically-panned remake of The Front Page with Matthau and Neil Simon’s Prisoner of Second Avenue, neither successfully.

But there was still gas in the tank, and in short order, he made two of his best movies The China Syndrome and Missing, both Golden Globe Best Motion Picture-Drama nominees for which he was nominated for both as best actor in a drama. All told Jack received 22 nominations winning four times, easily the most nominated male actor of all time.

After that, there were consistently fine performances (Glengarry Glen Ross) and a run of successful comedies with Matthau (Grumpy Old Men) but Lemmon knew his heyday was over, and he accepted it gracefully.

He won his last Golden Globe in 2000 as Best Actor in a TV film Inherit the Wind and died unexpectedly a year later, after completing an uncredited narration for Robert Redford’s Legend of Bagger Vance. He received his Cecil B. deMille award in 1991 presented to him by his devoted friend Walter Matthau.

A fitting tribute to an amazing acting career.