- Industry

Hollywood Between Art and Commerce

Last week’s billion-dollar signing by Warner Brothers of producer-directors JJ Abrams and John Wells to production deals may well be the culmination of the long struggle for actors and directors to earn a share of studio profits. Nowhere before in history have art and commerce melded together like in cinema. From the very beginning, the Seventh Art was also an industry. And in Hollywood money was never just a mere afterthought to creativity.

Nevertheless, MGM’s slogan was Ars Gratia Artis, Art for art’s sake, and studio assumed their contract players believed that. So for the first half of the last century, actors and directors were content just punching time cards for the studios. They were happy with their salaries, maybe less happy with the taxes they were paying in the second half of the century. But certainly money wasn’t their motivation. The one exception was James Cagney who forced Warner Brothers’ hand but ended up the worse for that.

True some them took advantage of tax shelters (oil drilling for example) but even those backfired. As early as 1919 Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin had created their own studio, United Artists, but even that venture never made any of them very rich.

The one success story was Samuel Goldwyn, who a year later, started financing his own movies and ended up arguably the wealthiest of all Hollywood legends. Another was Greta Garbo. She never got a percentage of her movies or sought ownership, but before quitting acting abruptly in 1942, she was Hollywood’s highest-paid Hollywood actress, and when she died 40 years later she left a considerable estate thanks to wise investments.

But by 1950 the face of Hollywood had changed. Not just because of the impact of television, which had decimated movie attendance, but because of the Supreme Court antitrust ruling of 1948 which effectively dismantled the Hollywood system by prohibiting studios from monopolizing theater exhibition as well as distribution and production. Another blow came even later in 1962 when the justice dept. forced a separation of the largest talent agency MCA and Universal which it owned.

This led Lew Wasserman (who ran both) to encourage his stable of talent to enter into production deals with the studios. He expanded on a practice established in the 1930s whereby an actor could pay much less tax by turning himself into a corporation, which was taxed at a much lower rate than personal income. Wasserman used this tax avoidance scheme with actor James Stewart, beginning with the Anthony Mann western Winchester ’73 (1950). This marked the first time an onscreen talent ever received ‘points in the film” – a business tactic that skyrocketed after Wasserman’s negotiation and Stewart’s ensuing success.

Wasserman was indeed a game changer. He encouraged his other clients Doris Day, Rock Hudson, and Alfred Hitchcock to do the same.

Before that only a few actors seemed bent on securing their financial future. The two that come to mind are Cecil B. deMille winners Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas, who separately formed production companies which produced the films they starred in. But for the most part, the really big stars cared less about commerce than art. Cary Grant, arguably the richest actor of the 1930s and 40s accumulated his wealth not by venturing into production but by signing lucrative deals with different studios and making three or four movies a year. Other great stars like Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Greer Garson, Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, and Marlene Dietrich, however, were quite content to just make movies as long as they were well paid for their labor.

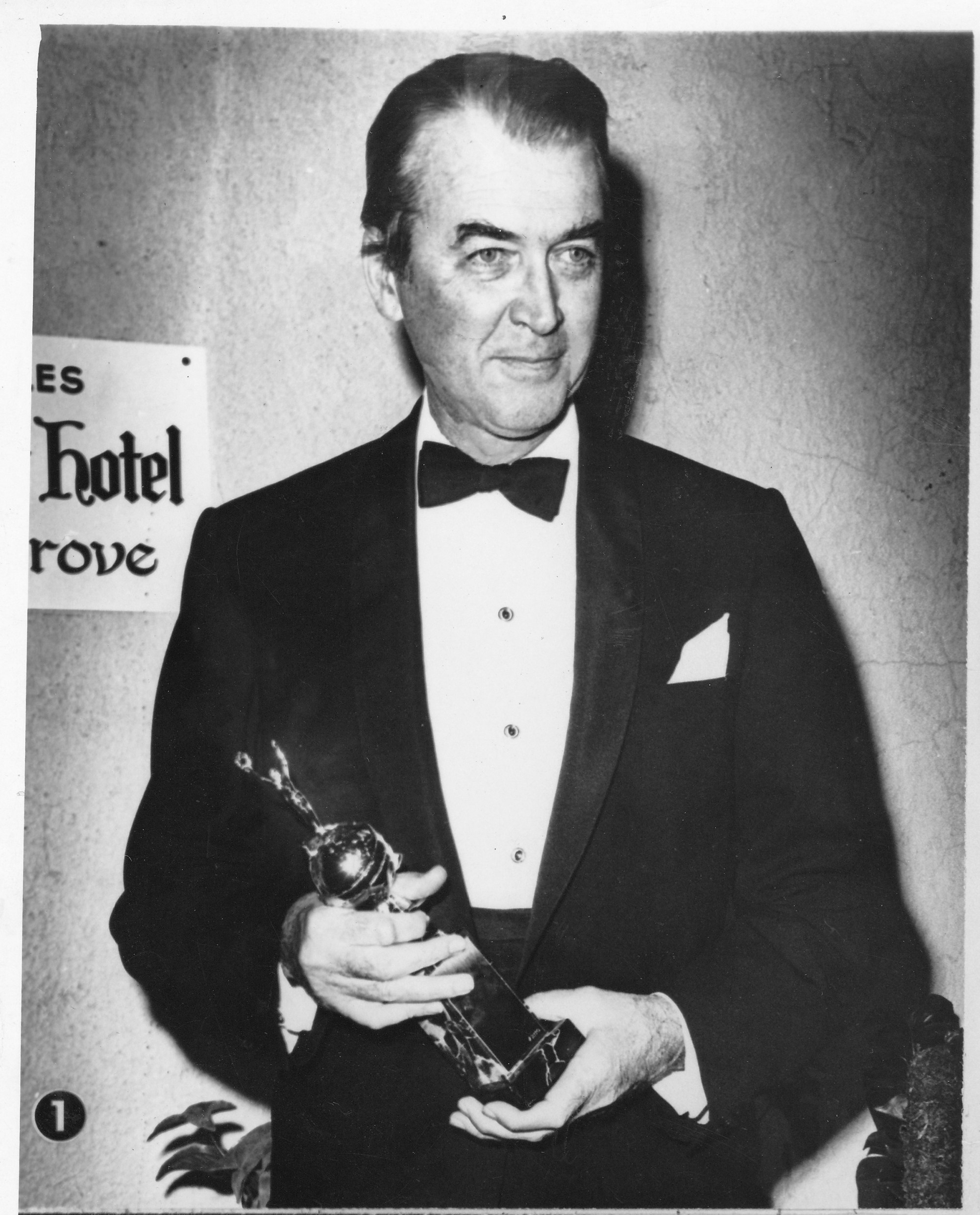

John Wayne, another Cecil B. deMille winner, formed Batjac, his production company, but for the most part, actors stuck to acting. A few took advantage of tax shelters, most notably the Burtons, Elizabeth, and Richard, who domiciled themselves in Switzerland, to avoid paying taxes.

Ironically people behind the camera, the producers and directors, who should have been at an advantage, had even less success when they ventured into independent production. For example Jerry Wald, who produced Mildred Pierce and Golden Globe winner Johnny Belinda. Once he was released from his servitude at Warner Bros., he set up his production company at RKO but with little success.

Even the formidable David O. Selznick who pioneered independent productions as early as 1935 eventually had to sell his Selznick Releasing Company assets to Warner Bros He died in 1965 spared of witnessing the sale of his Gone with the Wind to Ted Turner for peanuts.

Today’s stars have learned from their predecessor’s mistakes, quietly amassing fortunes as engines of their own brands. So we’re told that Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tom Hanks, and Clint Eastwood are worth in excess of $300 million, and George Clooney and Tom Cruise as much as $500 million.

And yet behind the curtain, the struggle continues, witness the current tension between WGA screenwriters and the agents who represent them over the packaging of their films to the studios. Commerce, ever the pressing handmaiden of Hollywood art.